Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125

Composition and premiere: Beethoven wrote his Ninth Symphony at the request of the Philharmonic Society of London, composing the piece between 1822 and 1824. The premiere took place May 7, 1824, Kärntnerthor Theater, Vienna, with the deaf composer on stage beating time, but Michael Umlauf conducting; Henriette Sontag, Karoline Unger, Anton Haitzinger, and Joseph Seipelt were the soprano, alto, tenor, and bass soloists. First BSO performance: Georg Henschel conducting at the end of the orchestra’s first season in March 1882. First Tanglewood performance: Serge Koussevitzky conducting, performance to inaugurate the Music Shed on August 4, 1938.

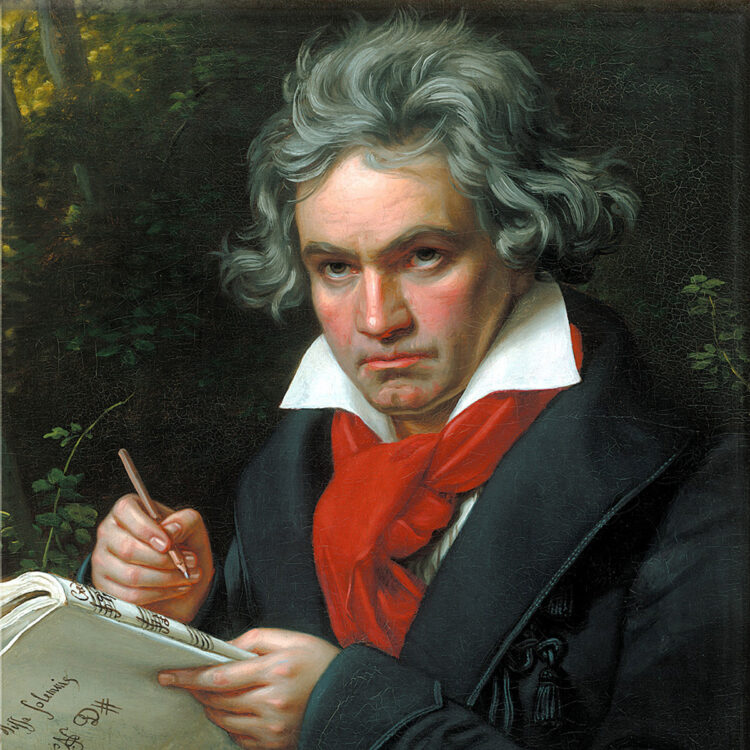

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in D minor is one of the most beloved and influential of symphonic works, and one of the most enigmatic. Partly it thrives in legends: the unprecedented introduction of voices into a symphony, singing Schiller’s “Ode to Joy”; the Vienna premiere in 1824, when the deaf composer could not hear the frenzied ovations behind him; the mystical beginning, like matter coalescing out of the void, that would be echoed time and again by later composers—Brahms, Bruckner, Mahler. Above all there is the choral theme of the last movement, one of the most familiar tunes in the world.

On the face of it, that in his last years Beethoven would compose a paean to joy is almost unimaginable. As early as 1802, when he faced the certainty that he was going deaf, he cried in the “Heiligenstadt Testament”: “For so long now the heartfelt echo of true joy has been a stranger to me!” Through the next twenty years before he took up the Ninth, he lived with painful and humiliating illness. The long struggle to become legal guardian of his nephew, and the horrendous muddle of their relationship, brought him to the edge of madness.

The idea of setting Schiller’s Ode to music was actually not a conception of Beethoven’s melancholy last decade. The poem, written in 1785 and embodying the revolutionary fervor of that era, is a kind of exalted drinking song, to be declaimed among comrades with glasses literally or figuratively raised. Schiller’s utopian verses were the young Beethoven’s music of revolt; it appears that in his early twenties he had already set them to music.

In old age we often return to our youth and its dreams. In 1822, when Vienna had become a police state with spies everywhere, Beethoven received a commission for a symphony from the Philharmonic Society of London. He had already been sketching ideas; now he decided to make Schiller’s fire-drunk hymn to friendship, marriage, freedom, and universal brotherhood the finale of the symphony. Into the first three movements he carefully wove foreshadowings of the “Joy” theme, so in the finale it would be unveiled like a revelation.

The dramatic progress of the Ninth is usually described as “darkness to light.” Scholar Maynard Solomon refines that idea into “an extended metaphor of a quest for Elysium.” But it’s a strange darkness and a surprising journey.

The first movement begins with whispering string tremolos, as if coalescing out of silence. Soon the music bursts into figures monumental and declamatory, and at the same time gnarled and searching. The gestures are decisive, even heroic, but the harmony is a restless flux that rarely settles into a proper D minor, or anything else. What kind of hero is rootless and uncertain? The recapitulation (the place where the opening theme returns) appears not in the original D minor but in a strange D major that erupts out of calm like a scream, sounding not triumphant but somehow frightening. As coda there’s a funeral march over an ominous chromatic bass line. Beethoven had written funeral marches before, one the second movement of the Eroica Symphony. There we can imagine who died: the hero, or soldiers in battle. Who died in the first movement of the Ninth?

After that tragic coda comes the Dionysian whirlwind of the scherzo, one of Beetho-ven’s most electrifying and crowd-pleasing movements, also one of his most complex. Largely it is manic counterpoint dancing through dazzling changes of key, punctuated by timpani blasts. In the middle comes an astonishing Trio: a little wisp of folksong like you’d whistle on a summer day, growing through mounting repetitions into something hypnotic and monumental. So the second movement is made of complexity counterpoised by almost childlike simplicity—a familiar pattern of Beethoven’s late music.

Then comes one of those singing, time-stopping Adagios that also mark his last period. It is alternating variations on two long-breathed, major-key themes. The variations of the first theme are liquid, meandering, like trailing your hand in water beside a drifting boat. There are moments of yearning, little dance turns, everything unfolding in an atmosphere of uncanny beauty.

The choral finale is easy to outline, hard to explain. Scholars have never quite agreed on its formal model, though it clearly involves a series of variations on the “Joy” theme. But why does this celebration of joy open with a dissonant shriek that Richard Wagner called the “terror fanfare,” shattering the tranquility of the slow movement? Then the basses enter in a quasi-recitative, as if from an oratorio but wordless. We begin to hear recollections of the previous movements, each rebuffed in turn by the basses: opening of the first movement…no, not that despair; second movement…no, too frivolous; third movement…nice, the basses sigh, but no, too sweet. (Beethoven originally sketched a singer declaiming words to that effect, but he decided to leave the ideas suggested rather than spelled out.) This, then: the ingenuous little Joy theme is played by the basses unaccompanied, sounding rather like somebody (say, the composer) quietly humming to himself. The theme picks up lovely flowing accompaniments, begins to vary. Then, out of nowhere, back to the terror fanfare. Now in response a real singer steps up to sing a real recitative: “Oh friends, not these sounds! Rather let’s strike up something more agreeable and joyful.”

Soon the chorus is crying “Freude!”—“Joy!”—and the piece is off, exalting joy as the god-engendered daughter of Elysium, under whose influence love could flourish, humanity unite in peace. The variations unfold with their startling contrasts. We hear towering choral proclamations of the theme. We hear a grunting, lurching military march heroic in context (“Joyfully, like a hero toward victory”) but light unto satiric in tone, in a style the Viennese called “Turkish.” That resolves inexplicably into an exalted double fugue. We hear a kind of Credo reminiscent of Gregorian chant (“Be embraced, you millions! Here’s a kiss for all the world!”). In a spine-tingling interlude we are exhorted to fall on our knees and contemplate the Godhead (“Seek him beyond the stars”), followed by another double fugue. The coda is boundless jubilation, again hailing the daughter of Elysium.

So the finale’s episodes are learned, childlike, ecclesiastical, sublime, Turkish. In his quest for universality, is Beethoven embracing the ridiculous alongside the sublime? Is he signifying that the world he’s embracing includes the elevated and the popular, West and East? Does the unsettled opening movement imply a rejection of the heroic voice that dominated his middle years, making way for another path?

In a work so elusive and kaleidoscopic, a number of perspectives suggest themselves. One is seeing the Ninth in light of its sister work, the Missa Solemnis. At the end of Beethoven’s Mass the chorus is declaiming “Dona nobis pacem,” the concluding prayer for peace, when the music is interrupted by the drums and trumpets of war. Just before the choir sings its last entreaty, the drums are still rolling in the distance. The Mass ends, then, with an unanswered prayer.

Beethoven’s answer to that prayer is the Ninth Symphony, where hope and peace are not demanded of the heavens. Once when a composer showed Beethoven a work on which he had written “Finished with the help of God,” Beethoven wrote under it: “Man, help yourself!” In the Ninth he directs our gaze upward to the divine, but ultimately returns it to ourselves. Through Schiller’s exalted drinking song, Beethoven proclaims that the gods have given us joy so we can find Elysium on earth, as brothers and sisters, husbands and wives.

In the end, though, the symphony presents us as many questions as answers, and its vision of utopia is proclaimed, not attained. What can be said with some certainty is that its position in the world is probably what Beethoven wanted it to be. In an unprecedented way for a composer, he stepped into history with a great ceremonial work that doesn’t simply preach a sermon about freedom and brotherhood, but aspires to help bring them to pass. Partly because of its enigmas, so many ideologies have claimed the music for their own; over two centuries Communists, Christians, Nazis, and humanists have joined in the chorus. Leonard Bernstein conducted the Ninth at the celebration of the fall of the Berlin Wall, and what else would do the job? Now the Joy theme is the anthem of the European Union, a symbol of nations joining together. If you’re looking for the universal, here it is.

One final perspective. The symphony emerges from a whispering mist to fateful proclamations. The finale’s Joy theme, prefigured in bits and pieces from the beginning, is almost constructed before our ears, hummed through, then composed and recomposed and decomposed. Which is to say, the Ninth is also music about music, about its own emerging, about its composer composing. And for what? “Be embraced, you millions! This kiss for all the world!” run the telling lines in the finale, in which Beethoven erected a movement of monumental scope on a humble little tune that anybody can sing, and probably half the world knows.

The Ninth Symphony, forming and dissolving before our ears in its beauty and terror and simplicity and complexity, is itself Beethoven’s embrace for the millions, from East to West, high to low, naive to sophisticated. When the bass soloist speaks the first words in the finale, an invitation to sing for joy, the words come from Beethoven, not Schiller. It’s the composer talking to everybody, to history. There’s something singularly moving about that moment when Beethoven greets us person to person, with glass raised, and hails us as friends.

JAN SWAFFORD

Jan Swafford is a prizewinning composer and writer whose most recent book, published in December 2020, is Mozart: The Reign of Love. His other acclaimed books include Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph, Johannes Brahms: A Biography, The Vintage Guide to Classical Music, and Language of the Spirit: An Introduction to Classical Music. He is an alumnus of the Tanglewood Music Center, where he studied composition.