Symphony No. 7

Composition and premiere: Beethoven began his Symphony No. 7 in the fall of 1811, completed it on April 13, 1812, and led the first performance on December 8, 1813, in the auditorium of the University of Vienna. First BSO performance: February 4, 1882, Georg Henschel conducting, during the orchestra’s first season, since which time the orchestra has performed the piece more than 470 times. First Tanglewood performance: August 5, 1939, Serge Koussevitzky conducting the BSO.

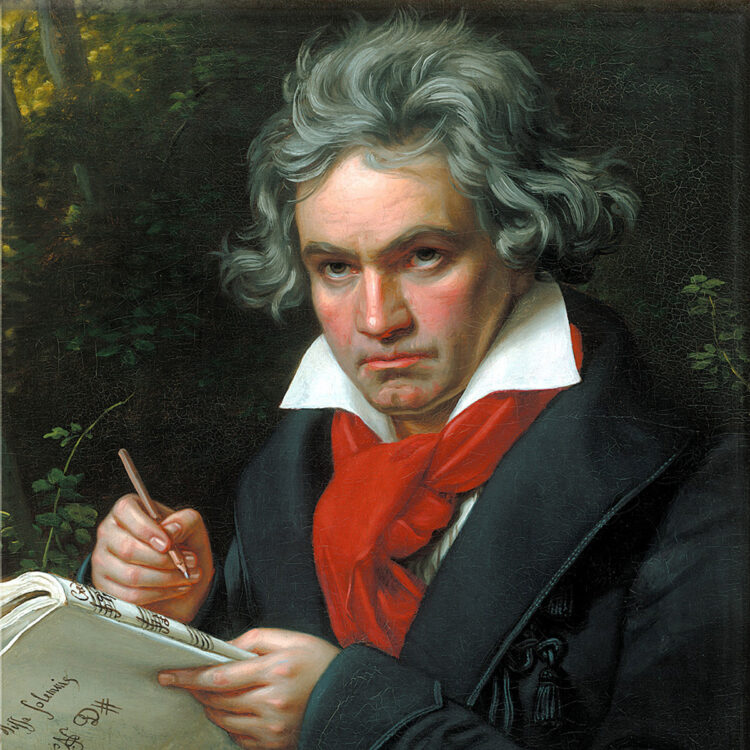

By 1812 much had changed in Beethoven’s life and career since the extraordinary period between 1802 and 1809, when he produced a flood of masterpieces perhaps unprecedented in the history of music. In 1809, however, around the time of the premiere of the Fifth and Sixth symphonies, this stupendous level of production abruptly fell off. Though there was much extraordinary music to come, Beethoven never again composed with the kind of fury he possessed in the first decade of the century.

What happened? Beethoven was increasingly ill and his bad hearing getting worse. However, given his ability to transcend physical misery, it is more likely that his decline in production came from expressive quandaries. He had begun to sense that the train of ideas that had sustained him through the previous decade was close to being played out. He had to find something new.

It is in the Seventh and Eighth symphonies that we see the turn toward the third period taking shape. In the Seventh Beethoven put aside for good the heroic model of the Third and Fifth symphonies, but he had not yet arrived at the inward music of the late works.

If not heroic or sublime, then what for the Seventh? A kind of Bacchic trance, dance music from beginning to end. Wagner called it “the apotheosis of the dance.” But the Seventh dances unlike any symphony before: it dances wildly and relentlessly, dances almost heroically, dances in obsessive rhythms whether fast or slow. Nothing as decorous as a minuet here; it’s rather shouting horns and skirling strings (skirling being what bagpipes do).

The symphony’s expansive and grandiose introduction strikes a note at once appropriate and misleading: the fast dance that eventually starts out from it seems something of a surprise. But from the introduction’s slow-striding opening theme many other melodies will flow. Above all the introduction defines the symphony in its harmonies: wandering without being restless so much as brash and audacious, with a tendency to leap nimbly from key to key by nudging the bass up or down a notch. And the introduction defines key relationships to be thumbprints of late Beethoven: around the central key of A major he groups F major and C major, keys a third up and a third down. That group of keys will persist through the symphony, just as D and B-flat persist in the Ninth.

With a coy transition from the introduction, we’re off into the first-movement Vivace, quietly at first but with rapidly mounting intensity. The movement is a titanic gigue. Its dominant dotted rhythmic figure is as relentless as the Fifth Symphony’s famous figure, but here the effect is mesmerizing rather than fateful. Rhythm plays a more central role than melody here, though there is a pretty folk tune in residence. More, though, the music is engaged in quick changes of key in startling directions, everything propelled by the rhythm. From the first time you hear the symphony’s outer movements, meanwhile, you never forget the lusty and rollicking horns.

Nor are you likely to forget the first time you hear the stately and mournful dance of the second movement, in A minor. It has been an abiding hit and an object of near-obsession since its first performances. The idea is a process of intensification, adding layer on layer to the inexorably marching chords (with their poignant chromaticism that Germans call moll-Dur, minor-major). Once again, in a slowish movement now, the music is animated by an irresistible rhythmic momentum. For contrast comes a sweet, harmonically stable B section in A major (plus C, a third up). Rondo-like, the opening theme returns twice, lightened, turned into a fugue, the last time serving as coda.

The scherzo is racing, eruptive, giddy, its main theme beginning in F major and ending up a third in A, from one flat to three sharps in a flash. We’re back to brash shifts of key animated by relentless rhythm. The Trio provides maximum contrast, slowing to a kind of majestic dance tableau, as frozen in harmony and gesture as a painting of a ball. The Trio occurs twice and jokingly feints at a third time before Beethoven slams the door.

The purpose of the finale seems to be, amazingly, to ratchet the energy higher than it has yet been. If earlier we have had exuberance, brilliance, stateliness, those moods of dance, now we have something on the edge of delirium, in the best and most intoxicating way: stamping and whirling two-beat fiddling, with the horns in high spirits again. Does any other symphonic movement sweep you off your feet and take your breath away so nearly literally as this one?

The Seventh was premiered in December 1813 as part of the ceremonies around the Congress of Vienna, when the aristocracy of Europe gathered with the intention of turning back the clock to before Napoleon. Beethoven would despise the reactionary results of the Congress, but that was in the future; he was glad to receive its applause. The premiere of the Seventh under his baton was one of the triumphant moments of his life. For the first of many times, the slow movement had to be encored. The orchestra was fiery and inspired, suppressing their giggles at the composer’s antics on the podium. In loud sections (the only ones he could hear) Beethoven launched himself into the air, arms windmilling as if he were trying to fly; in quiet passages he all but crept under the music stand. The paper reported from the audience “a general pleasure that rose to ecstasy.”

It’s true that another piece premiered on the program, Beethoven’s trashy and opportunistic Wellington’s Victory, got more applause and in the next years more performances. But for the moment he was not too proud to bask a little, pocket the handsome proceeds, perhaps to enjoy with a sardonic laugh the splendid success of the bad piece and the merely bright prospects of the good one. The Seventh after all celebrates the dance, which lives in the ecstatic and heedless moment.

JAN SWAFFORD

Jan Swafford is a prizewinning composer and writer whose most recent book, published in December 2020, is Mozart: The Reign of Love. His other acclaimed books include Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph, Johannes Brahms: A Biography, The Vintage Guide to Classical Music, and Language of the Spirit: An Introduction to Classical Music. He is an alumnus of the Tanglewood Music Center, where he studied composition.