Symphonic Works of Wayne Shorter

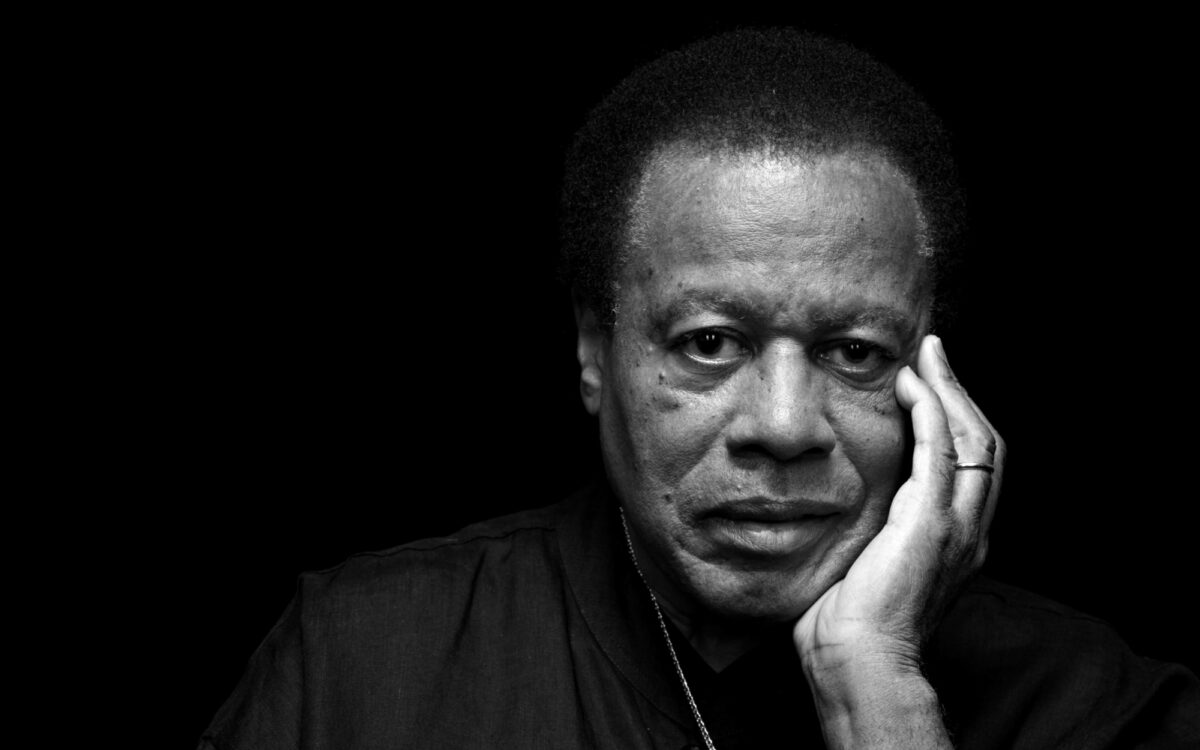

"The Symphonic Legacy of Wayne Shorter," by Michelle Mercer

In February 2022, the conductor Clark Rundell visited Wayne Shorter at his Hollywood Hills home, just after the final performance of Wayne’s opera …(Iphigenia) in Los Angeles. This visit was pivotal in two ways. Rundell learned there were no concert plans for the occasion of Wayne’s 90th birthday in August 2023, so he and Wayne started planning a celebratory orchestral tour. Wayne soon produced many long, black boxes filled with scores—and that’s when Rundell, the preeminent conductor of Wayne’s orchestral work, realized that Wayne had composed far more symphonic music than he’d ever imagined.

“I could probably name about six or seven titles,” Rundell remembers. “And I thought there may have been a couple more. It suddenly became clear that there was a lot more than that. Walking into Wayne’s house and finding all this music was like walking into a house in the south of France that nobody knew Picasso used to live in and there are just Picassos all over the wall. We got into a Houston, there’s a problem scenario. Because, you know, there were no copies of some of this music, and Wayne lives in California, where they have fires.”

Composer and …(Iphigenia) collaborator Phillip Golub stepped up to digitize Wayne’s symphonic music, with a grant from film composer James Newton Howard supporting his work. Golub copied 28 orchestral works and many other classical pieces besides; he began the process of getting the scores in shape to be published and available to orchestras worldwide.

Wayne Shorter passed away in March 2023 at age 89. Just before his transition, he expressed deep Buddhist conviction as he told his family, “It’s time to go get a new body and come back to continue the mission.” The Symphonic Side of Wayne Shorter is his mission continued, the 90th birthday celebration transformed into a joyous tribute tour for the jazz innovator, composer, bandleader, and saxophonist. The tour concludes with these Boston Symphony Orchestra concerts.

Wayne Shorter is widely regarded as one of jazz’s greatest composers. The fake book, or collection of sheet music for jazz musicians, features around thirty Wayne Shorter tunes, titles such as Footprints, Speak No Evil, Nefertiti, and Witch Hunt. Wayne—like Monk, Miles, and Duke, he has single-name status among jazz fans—wrote many of these beloved standards for the 1960s sextets or quintets of Art Blakey and Miles Davis, in which he played tenor saxophone as memorably as he composed. Other musical gems appeared on Wayne’s own 1960s Blue Note albums, which are among the most revered recordings in all of jazz.

Yet Wayne’s symphonic side as a composer also was long evident in his influences, the sheer scope of his ambition, and his readiness to take full advantage of any expanded instrumentation.

Wayne was born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1933. His earliest memories were of playing with clay at the kitchen table, sculpting not just one or two figures but endeavoring to create “the whole world.” As a boy, Wayne loved the cinema, finding special enchantment in the soundtracks for science fiction films: “The music behind Bela Lugosi when he played Igor in Son of Frankenstein. Or The Wolfman, that music behind Lon Chaney when he changed into the werewolf…that stuff got me curious about sound.” After seeing a film, Wayne and his brother Alan would reenact favorite scenes and test each other on how much of an entire soundtrack they could recall. “We called it ‘Say About,’” Wayne said. “Alan would wake me up in the middle of the night and say, ‘Want to Say About?’ Then we’d remember dialogue, sound effects, and the music. All with our voices and fingers.” His memory for music was as enduring as it was capacious. For the rest of his life, the mere mention of an obscure 1940s or ‘50s movie title could get Wayne singing whole sections of its soundtrack from memory.

While attending Newark Arts High, Wayne fell in love with jazz. He briefly played the clarinet before settling on the tenor saxophone, forming a bebop band and engaging in musical battles against “square” swing groups. Wayne then attended NYU, where, as a music education major, he studied such subjects as orchestration, music history, and modern harmony. The latter course inspired him to mix musical styles and challenge convention in his first compositions. But New York’s exciting jazz club scene soon lured Wayne away from a teaching career.

In 1959, Wayne joined Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, a hard bop quintet of trumpet, saxophone, piano, bass, and drums. Wayne quickly became the group’s resident composer as well as its saxophonist, writing hard-hitting tunes that were central to Messengers recordings. “I knew that I couldn’t write anything too filmy or ethereal,” Wayne said. “I had to write for impact.” Still, in 1961, when Art Blakey added a trombone to the Messengers’ line-up, Wayne immediately seized upon the new horn’s possibilities by writing tunes like “Children of the Night.” Its rich chord voicings gave only three horns an expansive sonority that at times could sound like a full orchestra—and eventually, Wayne would in fact arrange it for orchestra.

In 1964, Miles Davis recruited Wayne for his second great quintet. Miles gave him one instruction: “Bring the book.” Miles wanted Wayne’s compositions. As a lover of European harmonies, Miles was especially fond of Wayne’s harmonic sophistication. Their bandmate, bassist Ron Carter, explained it this way: “Wayne seems so aware of how the harmony affects form. I think Wayne’s sense of chord progressions is different than everybody else’s, but he writes them in a form where these chords, as unusual as they may seem, sound perfectly normal for that form.” Wayne’s composition operated on its own unique but elegant logic.

He distinguished himself as a saxophonist as well as a composer. “Improvisation is just composition sped up,” Wayne often said. He played impromptu solos with humor, suspense, melancholy, classical music themes, old jazz quotes, melodic displacements, the microcosmic, macrocosmic—and repeated variations on all of the above. “With Miles,” Wayne said. “I felt like a cello, I felt the viola, I felt liquid, dot-dash, and colors started really coming.” Wayne’s saxophone playing was so attentive to a composition’s big picture that the poet Paul J. Harding started calling Wayne “Robin Hood”: “Wayne stole the notes and gave them back to the music. Dig.”

In 1971, Wayne and the keyboardist Joe Zawinul formed the fusion group Weather Report, combining rock music’s visceral energy and instrumentation with jazz improvisation. Wayne heard the synthesizer representing an orchestra and went epic in his composition. He started writing what he called “music for films that would never be made.” As Zawinul cut down Wayne’s vast scores for the practical necessities of performing to Weather Report’s stadium crowds, he’d often tell Wayne he should be writing for chamber ensembles and orchestras.

At the end of Wayne’s years with Weather Report, his symphonic side emerged on three 1980s solo albums: Atlantis, Phantom Navigator, and Joy Ryder. Working alone, Wayne said he felt like that kid playing with clay again. “I said to myself, I’ve got to get back to that whole world perspective,” remembered Wayne. “So my music was multi-output, and I varied or reiterated lines in different ways to celebrate the discovery of eternal energy.” When Wayne had a chance to unleash all the music in his mind, he went symphonic with layered melodies and motifs—though still in a fusion setting, with electronic instruments realizing his musical concepts. His synthesized symphonies continued on Wayne’s 1995 album High Life, where he combined electric instruments with an actual orchestra.

In the late ‘90s, Wayne started receiving commissions to compose for symphony orchestras. At 65, the age of retirement, the start of career retrospectives for many artists, Wayne was just beginning to realize some of his deepest ambitions. In Wayne’s conception, no composition was ever really finished; revision could always make it new again. Some of his first symphonic works were rearrangements of “Angola” from his Blakey days, “Orbits” from his Miles years, and “High Life,” the title track from what was then his most recent recording. In performances, Wayne paired his own improvising acoustic jazz quartet with orchestras playing his through-composed scores, aiming to synthesize improvisation and composition in a new way.

By the aughts, Wayne was well-known for his mystical aspect. Experiencing much personal loss in the ‘80s and ‘90s, Wayne had looked to his Nichiren Buddhist practice for purpose and conviction. He chanted daily, and his music incorporated his spiritual practice. “For me, the word jazz means, ‘I dare you’,” he’d often say. “And this music, it’s dealing with the unexpected. No one really knows how to deal with the unexpected. How do you rehearse the unknown?” As profound as his intentions may have been, Wayne was never solemn. He spoke as colorfully as he soloed, influenced by the wordplay of Lester Young and other beboppers he’d idolized as a teenager. The childlike genius might discuss his collectible fairy figures coming alive at night, science fiction, and Norse mythology—and then leap to the subject of why 21st-century artists thinking outside the box was a form of political resistance, “especially if they lose the box altogether.” Wayne was generous in conversation, equally interested in building understanding with airport drivers, students, and the heads of state and royalty who bestowed major awards upon him. Nearly everyone who spoke even briefly with Wayne felt they’d had a special connection with him.

A crucial relationship in Wayne’s symphonic career began in 2008 when his quartet joined the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic under the direction of Clark Rundell. Rundell had headed the Royal Northern College of Music’s Jazz Studies department for seventeen years; he was deeply committed to new music, giving world premieres of works by Louis Andriessen, Steve Reich, and many others.

In Rundell, Wayne found a translator and champion. Rundell employed performance practices that bridged the jazz and classical worlds, giving Wayne’s orchestral music new grace and power. Wayne’s difficult works typically had been allotted only as much rehearsal time as easier pops material. Rundell first advocated for more days with an orchestra, even sometimes offering to cover his own expenses for the extra time. Rundell understood that in a contemporary classical world of exact notation, Wayne’s space for rhythmic, dynamic, and other interpretation required some major adjustments for orchestra musicians. Having secured adequate rehearsal time, Rundell would ask an orchestra to listen to and then imitate the phrasing and pulse of Wayne’s quartet, jazz’s felt elements that come to life beyond the printed page. With Clark Rundell at the helm, orchestras signed on for a Wayne Shorter program confident that the music would soar.

Wayne’s distinctive orchestral music has now been around for a couple of decades, long enough for everyone to relax into it a bit. Jazz drummer Terri Lyne Carrington has worked with Wayne for thirty-seven years in numerous settings, including some of his first orchestral concerts. “Every time musicians play Wayne’s orchestral music, we feel a little more at home with it,” Terri Lyne says. “Sometimes in the quartet out in front of the orchestra, you have to lead and follow at the same time. I’m following the melodies the orchestra is playing, then they’re listening to our rhythm section for cues. That’s the only way that it will work.”

Positioning Wayne’s work on the contemporary landscape feels like releasing helium balloons toward a specific destination. No comparison comes close to hitting the mark. We can say that Wayne knew his Stravinsky and Ravel intimately—often he’d have their scores open in his studio as he composed. We might hear Milhaud’s La Création du monde as a touchstone for Wayne’s opulent orchestration. Wayne is an American composer, though he may have more in common with Copland than a contemporary like John Adams. His harmonies and rhythms are jazz-oriented, but oriented toward his own innovations within the jazz idiom. Wayne’s symphonic side is indeed cinematic, not in any overt resemblance to film scores, but in how he cuts from one musical idea to another with audacity. In Wayne’s orchestral writing, the sage composer and jazz master meets the young boy who watched science fiction films, relishing their unknown worlds and element of surprise.

For esperanza spalding, his music’s resistance to comparison is what makes it so interesting:

We didn’t know for a long time about the massive interconnectivity of aspen groves and how their underground root systems actually make them the largest organisms on earth. Wayne’s imagination feels like that to me. I can look at all the component parts of his music and understand how it works, but there’s a part below or beyond that you can’t perceive or analyze. You feel that there’s something we can’t see that’s making all of that expression happen. And I think that’s what makes Wayne and his music so exciting and such an anomaly, you know?

Wayne certainly never gave instructions on how to hear his music. For him, the audience’s response was an essential, generative element of any performance. He would have been fiercely proud to occupy the same Symphony Hall seat that might once have held Béla Bartók. Wayne would have greeted audience members with curiosity and enthusiasm, ready to talk movies or politics—and above all, eager to know what they’d heard and felt as listeners tonight.

Wayne Shorter selected this program before he passed away. Except for Causeways, he orchestrated all these selections as well. The program features orchestral arrangements of music from throughout Wayne’s career.

Forbidden, Plan-It!

This opening piece was originally a fusion track on the 1987 album Phantom Navigator, Wayne’s homage to the 1956 sci-fi film Forbidden Planet. The orchestral version is rich in counterpoint with a touch of whimsy, evoking something of Stravinsky in Hollywood. We feel Wayne marching us into unknown worlds with “serious fun,” as Duke Ellington defined jazz’s spirit.

Orbits

Wayne first recorded “Orbits” on the 1967 album Miles Smiles. The piece also appeared in a larger ensemble setting on the Grammy-winning 2003 album Alegría, then again on the 2013 live quartet album Without a Net, when Wayne’s saxophone performance on “Orbits” won yet another Grammy for Best Improvised Jazz Solo (Wayne won 12 Grammys over his career).

Orbits is one of Wayne’s earliest symphonic arrangements, dating back to his first commissions. The piece leaves ample room for jazz improvisers to take turns playing variations on its theme, tracing paths over, under, around, and through the composition.

Midnight in Carlotta’s Hair

“Dusk began to fall, but it was already midnight in Carlotta’s hair.”

When Wayne came across this phrase in a fairy tale, he stopped cold. The phrase struck him as capturing an elusive quality of certain women and he set out to write music that would do the same. First appearing on Wayne’s 1995 album High Life, this version of Midnight in Carlotta’s Hair is among his most beloved orchestral works.

…(Iphigenia) Suite No. 1

As a college student in the early 1950s, Wayne began writing an opera called “The Singing Lesson,” a story of the Italian gangs he observed near the New York University campus in Greenwich Village. Wayne stopped working on this opera due to a conflict: “I heard that Leonard Bernstein was doing something called West Side Story, and I thought ‘I’ll catch up to mine some other time,’” Wayne said, implying that his opera was a little too similar to Bernstein’s now-famous musical. For decades, Wayne harbored a dream of writing another opera until he came upon the myth of Iphigenia.

In 2013, Wayne confessed his opera dream to esperanza spalding, sharing his ideas for adapting the ancient Greek tragedy. “He was struck by what he thought Euripides was saying about women,” says esperanza. “And so he wanted to write an opera dedicated to the true spirit and meaning and potential of this mythic figure.”

When Wayne’s health began to fail a few years later, esperanza took a leave of absence from her Harvard teaching position to move in with the Shorters and dedicate herself to Wayne’s opera full time. She and Wayne worked side by side on the libretto and music, respectively. esperanza invited three women of different ancestries to help write Iphigenia’s voice: Indigenous poet laureate Joy Harjo, author and poet Safiya Sinclair, and vocalist Ganavya Doraiswamy.

…(Iphigenia) premiered in Boston in 2021 with esperanza as lead vocalist and Clark Rundell conducting. This concert suite is extracted from the full opera.

Causeways

Among Wayne’s many fusion works with an orchestral heart, Clark Rundell was most struck by “Causeways” from the 1988 album Joy Ryder. Rundell asked Wayne if he might orchestrate the piece himself.

“Do it,” Wayne told him. “Just make it even more mysterious.”

Rather than emulate Wayne’s orchestration, Rundell arranged Causeways in his own style, featuring Wayne’s melody and hypnotic rhythm in a kind of Boléro. One aim was introducing a briefer Wayne Shorter composition to the symphonic repertoire: “Everybody needs a shorter piece lasting nine or ten minutes to play in front of The Rite of Spring or The Firebird Suite,” says Rundell. “An orchestra could play Causeways in the place of Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, for example. We put Causeways in this program ahead of Gaia, Wayne’s biggest and hardest piece—and maybe his grandest one.”

Gaia

The program ends triumphantly with this half-hour, Los Angeles Philharmonic-commissioned piece that debuted in 2013. Gaia was Wayne’s first collaboration with esperanza spalding. He composed Gaia expressly for esperanza and then invited her to write lyrics. She often tells this story:

When I was going over to Wayne and Carolina’s house often, I would be looking over his shoulder at the score. Wayne wrote all of his music by hand with a pen on score paper. He would use White Out and a ruler if he made a mistake. So I’m staring over his shoulder at this massive score of Gaia—he called it a tree trunk—and I said, “Wayne, what is this section about?” And he said, “This section is about people breaking through the cultural cobwebs and getting to their real transformative power. So I’m putting something really difficult in the third violin. Because usually, the third violin gets the really boring stuff. This will help them break through!” So that was the level of thought and intention Wayne was putting into every note, and I’m sure you can hear it.

Michelle Mercer

Michelle Mercer contributed to National Public Radio for 20 years and is the author of Footprints: The Life and Work of Wayne Shorter, among other books. Her Substack is michellemercer.substack.com.

History, instrumentation, and duration

The original version of Forbidden, Plan-It!, recorded in 1986 for Shorter’s 1987 Phantom Navigator album, was substantially scored for synthesizers and electronic versions of percussion and melodic instruments and soprano saxophone solo. Shorter’s orchestral score calls for piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (not specified), harp, piano, and strings (first and second violins, violas, cellos, and double basses). The piece is about 6 minutes long. As with all of these scores, a solo jazz ensemble can augment the standing orchestra score.

Orbits appeared originally with a very different, quick vibe on the Miles Davis Quintet album Miles Smiles in 1967. The present version is rooted in Shorter’s 2003 recording of the piece for his album Alegría. Yet another version for jazz quartet—which won a Grammy Award for Best Improvised Jazz Solo—appears on Shorter’s 2011 live album Without a Net. Shorter’s orchestral score calls for flute, oboe, English horn, clarinet, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, soprano & tenor saxophones, 2 horns, trumpet, guitar, bass guitar, piano, and strings. Orbits is about 6 minutes long.

Midnight in Carlotta’s Hair appeared on Shorter’s 1995 album High Life, which won the Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Jazz Performance. The original featured improvised solo saxophone with percussion, bass, piano, and a unison ensemble of winds, strings, and synthesizers playing the primary melody. Shorter’s orchestral score calls for flute, oboe, English horn, clarinet, bass clarinet, tenor saxophone, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, trumpet, trombone, strings, and unspecified “soloist” (in this case primarily esperanza spalding as vocalist). The piece is about 6 minutes long.

Causeways appeared on Shorter’s 1988 album Joy Ryder, which featured 23-year-old percussionist Terri Lyne Carrington in her first recording project with the composer. A largely unison melody in multiple instruments, including Shorter’s soprano sax, rises above an ensemble chord progression on a rhythmic ostinato (repeated pattern). The world premiere of Clark Rundell’s orchestral version of Causeways featured the quartet of Ravi Coltrane, saxophone; Danilo Peréz, piano; John Patitucci, bass, and Terri Lyne Carrington, drums, November 14, 2023, at the Elbphilharmonie, Hamburg, with the Hamburg Symphony Orchestra conducted by Clark Rundell. His orchestral score calls for piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 2 trombones, bass trombone, tuba, timpani, percussion (3 players: I. four suspended cymbals, bass drum; II. 2 tam-tams [medium, large], gong [low D], congas; III. vibraphone [optional]); jazz quartet (optional) of soprano saxophone, piano, bass, and drums, and strings. Causeways is about 9 minutes long.

The …(Iphigenia) Suite No. 1 was arranged and assembled by Clark Rundell from Wayne Shorter and esperanza spalding’s opera …(Iphigenia), the premiere of which was presented by ArtsEmerson, Boston, on November 12, 2021, led by Clark Rundell and featuring esperanza spalding. spalding based her libretto on Euripides’ ca. 407 BCE play Iphigenia in Aulis. The score of the suite calls for solo vocalist and jazz trio (piano, bass, drums) with an orchestra of 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), oboe, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, trombone, bass trombone, tuba, timpani, percussion (2 players: glockenspiel, vibraphone, triangle, 3 suspended cymbals [small, medium, large], bongos, tom-toms, snare drum), and strings. The suite is about 20 minutes long.

Gaia for jazz quartet and orchestra was commissioned by the Los Angeles Philharmonic, which premiered the piece with Wayne Shorter, saxophone; esperanza spalding, vocalist; Danilo Pérez, piano; John Patitucci, bass, and Brian Blade, drums, in February 2013 at Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, led by Vince Mendoza. esperanza spalding wrote the lyrics. In addition to the jazz soloists, the score of Gaia (as edited by Clark Rundell) calls for piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, 4 bassoons (3rd and 4th doubling contrabassoon), 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 4 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, piano, celesta, and strings. Gaia is about 28 minutes long.