Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat, Opus 73, Emperor

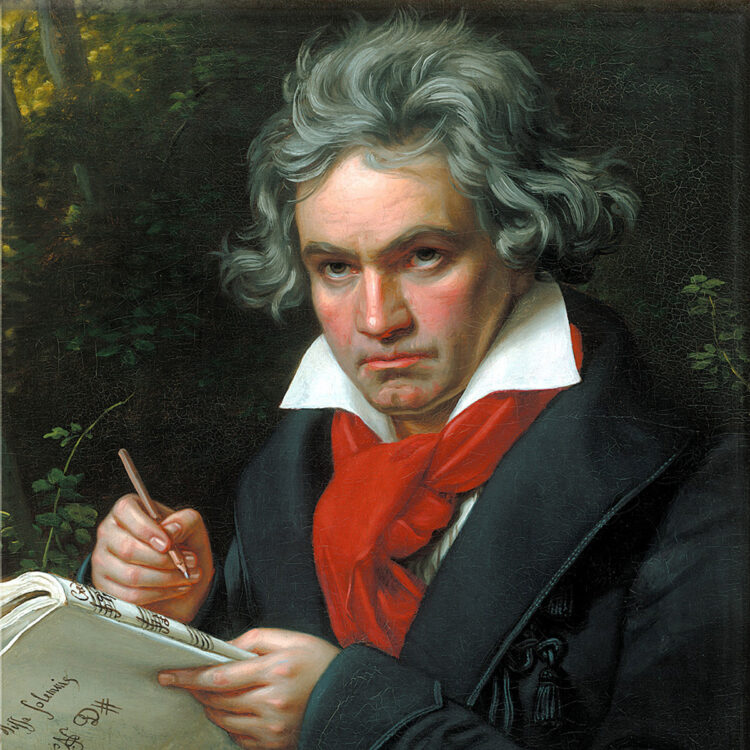

Ludwig van Beethoven was born in Bonn (then an independent electorate) probably on December 16, 1770 (he was baptized on the 17th), and died in Vienna on March 26, 1827.

Beethoven composed his Piano Concerto No. 5, Emperor, in 1809, but it was not performed in Vienna until February 12, 1812, when the soloist was Beethoven’s student Carl Czerny. The first known performance was given in Leipzig on November 28, 1811, by pianist Friedrich Schneider, with Johann Philipp Christian Schulz conducting the Gewandhaus Orchestra. The score, like many of his others (including the Fourth Piano Concerto), was dedicated by Beethoven to his patron, student, and friend, Archduke Rudolph. In addition to the solo pianist, the score calls for 2 each of flutes, oboes, clarinets, and bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings. The concerto is about 40 minutes long.

Beethoven wrote his first four piano concertos for himself, but by the premiere of the Fourth in 1807 his hearing was seriously atrophied and his career as a virtuoso coming to an end. So he never played the Piano Concerto No. 5, Op. 73, later dubbed the Emperor, written in 1808-9 and first performed in November 1811. It is dedicated to his patron, Archduke Rudolf, his student as composer and pianist. The majestic quality that gained the concerto its name is sometimes credited to the influence of its dedicatee and Rudolf’s exalted position—he was brother of the Emperor. A more likely reason for its tone is simply that Beethoven had written nothing like it, and he wanted maximum variety from his output in a given genre.

Like most Beethoven works, the Emperor lays out its essential character and ideas in the first seconds. It is in E-flat major, often a heroic key for him, and so it is here. We hear a fortissimo chord from the orchestra, which summons bravura torrents of notes from the piano. Here the radical departure from the Mozart model is less the idea of beginning with the soloist than in the cadenza-like quality that will mark much of the solo part. A second towering chord from the orchestra is answered by more heroic peals from the piano, this time sinking to some quiet espressivo phrases that foreshadow the second movement. Only then does the orchestra set out on the leading theme, a grand and sweeping military tune that will dominate the movement. By now it’s clear that this piece is symphonic in scope, heroic in tone, and the hero is the soloist. The appearance of a softly lilting second theme in the esoteric key of E-flat minor presages a work marked by unusual key shifts, their effect ranging from startling to mysterious.

After an opening more consistently militant in style than in any other Beethoven concerto, the second movement unfolds in a serenely spiritual atmosphere, beginning with an eloquent theme in muted strings that Beethoven’s pupil Carl Czerny said was based on pilgrims’ hymns.

The rondo finale begins with a lusty, offbeat theme in the piano. Call its tone playfully heroic. As in the first movement, the opening theme dominates. Toward the end, a thrumming timpani accompanies what seems to be the approach of a cadenza, but once again there is none, because the soloist has been showing off all along. Beethoven’s last concerto ends with an ebullient burst of offbeat exclamations that land on the beat only at the last moment.

Beethoven later sketched toward another piano concerto, but it bogged down. By then, his sound world trapped in his own head by deafness, for him the public, theatrical genre of the concerto had no more place. The concertos are among the crowns of his middle period. Ahead were the sublime works of the late music: the Diabelli Variations and Hammerklavier Sonata for piano, the Missa solemnis and Ninth Symphony, the late string quartets. One can muse on how a final concerto might have fit into that epic company.

Jan Swafford

Jan Swafford is a prizewinning composer and writer whose most recent book, published in December 2020, is Mozart: The Reign of Love. His other acclaimed books include Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph, Johannes Brahms: A Biography, The Vintage Guide to Classical Music, and Language of the Spirit: An Introduction to Classical Music. He is an alumnus of the Tanglewood Music Center, where he studied composition.

The first American performance was given at the Boston Music Hall on March 4, 1854, with pianist Robert Heller and the orchestra of the Germania Music Society under the direction of Carl Bergmann.

The first Boston Symphony performance featured Carl Baermann under the direction of Georg Henschel on January 28, 1882, during the BSO’s first season.