Piano Concerto No. 4 in G, Opus 58

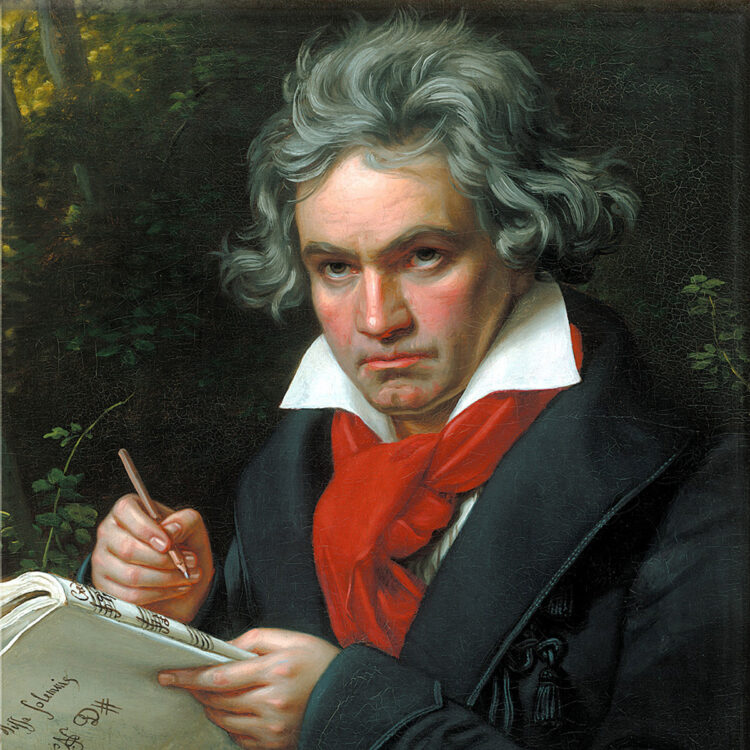

Ludwig van Beethoven was baptized in Bonn, Germany, on December 17, 1770, and died in Vienna on March 26, 1827. He composed the Fourth Piano Concerto, Opus 58, in 1805 and early 1806 (it was probably completed by spring, since his brother offered it to a publisher on March 27). The first performance was a private one, in March 1807, at the home of his friend and patron Prince Lobkowitz. The public premiere took place at Vienna’s Theater-an-der-Wien on December 22, 1808, with the composer as soloist, in the same famous concert that included, among many other things, the premieres of his Fifth and Sixth symphonies.

In addition to the solo piano, the score calls for an orchestra of 1 flute, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, and strings, with 2 trumpets and timpani added in the finale.

It was foreordained that Beethoven would write piano concertos. By the time he reached maturity as a composer he was already one of the greatest keyboard players in the world, and in those days virtuosos generally wrote concertos for themselves as part of their repertoire. For that reason, traditionally the genre was not taken particularly seriously in musical terms. It was a vehicle with which to show off one’s prowess. But Mozart broke with that tradition; his piano concertos are among his finest and most ambitious works. Given that Mozart was one of his prime models in all things musical, Beethoven would naturally start in his predecessor’s footsteps—and eventually continue on his own path.

Beethoven’s career was intimately bound up with the keyboard, from his teens in Bonn as a budding soloist to his years as a composer/pianist in Vienna. He was part of the first generation to grow up playing the instrument, which had only recently replaced the harpsichord and was evolving rapidly. The consummate professional, Beethoven paid minute attention to finding idiomatic ways of playing and composing for the piano. Meanwhile he was an advisor to piano makers, who listened to what he said. Mostly what he told them was to make their instruments bigger and stronger. His music said the same thing; the force of his conceptions demanded louder and richer instruments with a wider range of notes.

As a performer Beethoven was celebrated for the power and velocity of his playing, the brilliance of his ornaments including double and triple trills, and above all the fire and imagination of his improvisations. Years before his music started to define the Romantic temperament, that wild and passionate spirit was prophesied in the music that flowed directly from his mind to his fingers. As for concertos, in the pattern common to Mozart and most composer/performers, he needed to keep a fresh one in his repertoire, written to strut his particular stuff. He didn’t publish his early piano concertos right away; they were for his own use, and he tinkered with them from performance to performance. When one concerto had lost its novelty he wrote another, and only then published the earlier one.

As an artist Beethoven was as much a traditionalist as a radical. Especially in his early career, he had models for most of his efforts and considered it his business to master the norms of his craft, to understand the individual nature of each genre, and on that foundation to forge his own path and make his own statement. Until he was ready for that statement, he bided his time. He knew that his models were also going to be his competition. His string quartets would be up against Haydn’s, his concertos up against Mozart’s. So when his works were going to be measured against the finest of their kind, he was cautious: his first string quartets are masterful but not notably bold; he was not yet ready to compete with Haydn. His solo piano music was bolder earlier, because he considered the keyboard music of Haydn and Mozart to be more redolent of harpsichord than piano.

None of this is to say that Beethoven was afraid of anybody. But as a practical and professional matter, until he saw his path clearly he was not going to issue ambitious work to challenge the competition past or present. His first two piano concertos are a case in point; in tone they are very much general late-18th-century, not overtly Mozartian, but with novel touches that at the time raised eyebrows. His Third Concerto, later understood as the transition to the mature Beethoven voice of the last two concertos, is the most audibly indebted to Mozart. With the Fourth Concerto of 1806, he was ready to make his statement.

If the first three piano concertos have the spirit of the Mozart concertos in various degrees hanging over them, in the Piano Concerto No. 4 in G, Opus 58, from 1805-6, that spirit lingers, but the sound and effect are unmistakably Beethoven in the heart of his maturity. This is a work innovative and bold, with a singular integration of introspection and bravura. Well before Beethoven, a prime issue of concertos had been the relationship of soloist and orchestra: are they cooperating or competing? The Fourth Concerto lifts that drama to an unprecedented intensity.

Rather than the usual orchestral introduction, it begins with piano alone, the soloist brooding in a phrase of inward and reverberant simplicity. After the piano soliloquy the orchestra begins a nominally normal orchestral exposition, but there are two odd things about that entrance: its version of the piano theme is different from the piano version, and in the wrong key: B major. (It soon makes its way to the right key.) So from the beginning there is rift between orchestra and soloist: they don’t agree on the main subject or even its key. For the rest of the concerto that divide will play out in a variety of modes and moods.

The air of brooding nobility that the soloist establishes in the beginning is not otherwise its persona of the first movement, which is coltish, flighty, even mocking. The overall tone of the movement is stately and lyrical. During the development there are no particular hostilities, but at the recapitulation the soloist suddenly bursts out fortissimo with the original version of the main theme, which has not been heard since the opening. It is as if the soloist were shouting: No! This is how it goes!

That rift between solo and orchestra comes to a head in the second movement. Beginning with the piano alone, it proceeds in alternating phrases, the orchestra insistent, the soloist oblivious and inward. At the beginning the strings answer the soloist with a quiet, dotted military figure. The soloist responds quietly, molto cantabile. The solo part has returned to the brooding tone with which it opened the concerto. It is not interested in the military tread that the strings try to force on it in phrases of mounting belligerence. The soloist sighs, retreats, breaks out in roulades. The movement ends, if not in resolution, in some kind of truce.

The strings kick off the Vivace finale with a dashing rondo theme, but again in the wrong key, C major. It also happens to be a tune that the soloist cannot play: a piano is not capable of comfortably executing those fast repeating notes that are natural for a bowed instrument. Echoing the theme, all it can do is turn it into a pianistic version. So the original rivalry endures, but now played as comedy. After all the disputes and debates, near the end of an exuberant and vivacious finale, the resolution comes in a sublime stretch of singing E-flat major in divided violas, with piano garlands above. At the end all cheerily join the final chords together.

Jan Swafford

Jan Swafford is a prizewinning composer and writer whose most recent book, published in December 2020, is Mozart: The Reign of Love. His other acclaimed books include Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph, Johannes Brahms: A Biography, The Vintage Guide to Classical Music, and Language of the Spirit: An Introduction to Classical Music. He is an alumnus of the Tanglewood Music Center, where he studied composition.

The American premiere of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4 took place at the Boston Odeon on February 4, 1854, with soloist Robert Heller and the Germania Musical Society conducted by Carl Bergmann.

The first Boston Symphony performance of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4 was conducted by Georg Henschel on December 17, 1881, during the orchestra’s first season, with soloist George W. Sumner.