Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Opus 30

Composition and premiere: Rachmaninoff wrote his Piano Concerto No. 3 at Ivanovka, Russia, in summer 1909, completing it September 23, 1909. Rachmaninoff himself was soloist for the premiere on November 28, 1909, with the New York Symphony Orchestra conducted by Walter Damrosch, during the composer’s first American tour. The composer was also soloist in the first Boston Symphony Orchestra performances in October/November 1919, Pierre Monteux conducting. The first Tanglewood performance featured Byron Janis as soloist with Charles Munch leading the BSO on July 26, 1958.

For pianists, Rachmaninoff’s Third Piano Concerto stands as the ultimate challenge. Its herculean technical demands, titanic scale (the soloist plays almost non-stop for the entire 45 minutes), and emotional richness scared off such seasoned virtuosi as Joseph Lhévinne, Arthur Rubinstein, and Sviatoslav Richter. Even the pianist to whom it was dedicated, the composer’s friend Josef Hofmann, declined to play it, dismissing it as “more a fantaisie than a concerto.”

The concerto’s complexity at first confused and intimidated audiences and critics, too. In 1912, the usually well-informed Sergei Prokofiev, then a 21-year-old budding composer-pianist, wrote to a friend that he preferred Rachmaninoff’s “charming” Second Piano Concerto to the Third, which he found “dry, difficult, and unappealing. In musical circles it finds little affection, and besides the composer no one is performing it so far.” Only when another Russian pianist, Vladimir Horowitz, began to tour extensively did it start to win fans. Hearing him play the solo part for the first time, Rachmaninoff declared admiringly that Horowitz had “swallowed the concerto whole!” For Horowitz, it became something of a signature piece. Horowitz was also the first to record it, but in the late 1950s, a young and photogenic pianist from Texas—Van Cliburn—further popularized the concerto after his stunning victory at the 1958 Tchaikovsky Piano Competition in Moscow.

The Third Concerto emerged from a notably calm and happy period in Rachmaninoff’s life. The previous year he had conducted the triumphant premiere of his Second Symphony; eight years had passed since he completed his highly successful Piano Concerto No. 2. He was famous, wealthy, and happy in his family life. For the moment, Russia was at peace. For several years, Rachmaninoff had been spending winters in Dresden and summers at the idyllic estate of Ivanovka, deep in the steppes of Tambov province, more than 300 miles southwest of Moscow. In summer 1909, he was preparing there for an extensive and lucrative tour to the United States—his first—scheduled for autumn. With the proceeds he was planning to buy a car. For the tour he decided (at first secretly) to write a new concerto. Although afflicted in the past by severe bouts of depression that limited his ability to compose, on this occasion Rachmaninoff apparently worked quickly and easily, completing the entire piece in a matter of weeks. He practiced it on a dummy keyboard during the trans-Atlantic crossing in preparation for the premiere in New York in late November.

Rachmaninoff’s tour began in Northampton, Massachusetts, on November 4, 1909, and extended through late January 1910. The tour’s artistic highlight was the premiere of the new concerto in New York on November 28 and 30 with the New York Symphony Orchestra under Walter Damrosch. On January 16, it was repeated in Carnegie Hall with Gustav Mahler conducting.

In the Third Concerto, the piano dominates from start to finish. This distinguishes it from the Second, where the orchestra figures more prominently. The opening measures show the difference. In the Second Concerto, the piano begins with a bell-like tolling that introduces the orchestra and the main theme. In the Third, the orchestra provides a mere two measures of introduction before the soloist launches into the supple main theme. True, these first two measures contain a memorable gesture in dotted rhythm that emerges as a swelling motto, used throughout the concerto to considerable dramatic effect. The principal theme of the first movement begins on D, and then circles around it, unfolding leisurely over the long space of twenty-five bars. Some listeners have heard a folk origin or even a liturgical source in this elegant tune, but Rachmaninoff insistently claimed ownership: “It simply wrote itself! I wanted to ‘sing’ a tune on the piano like a singer does and find an appropriate orchestral accompaniment, that is, one that would not drown this ‘song.’ That’s all! Just the same, I find that, against my will, this theme does take on a songlike or familiar quality.”

The first movement’s main theme reappears in altered form (sometimes barely recognizable) throughout the concerto, in a manner reminiscent of the Symphony No. 2. The second theme—somewhat military in character—emerges with unusual subtlety out of the first. After an extended development section comes an enormous cadenza—or rather, two cadenzas, occupying five pages in the score. Rachmaninoff provided two alternatives for the soloist in the cadenza’s first part. The longer one (75 measures) was apparently composed first, while the other, somewhat shorter (59 measures) and less demanding, was added later. (The subsequent 21 measures are the same in both versions.) In performance, Rachmaninoff played the easier, shorter version. At the Tchaikovsky Competition in 1958, however, Van Cliburn made news by playing the original, longer version, launching a trend subsequently followed by other soloists.

For the second movement Rachmaninoff created a soulful, bleak, and melancholy main theme played first by the orchestra, a phrase falling gently into what sounds like the depths of despair. After thirty measures, the piano enters, initiating a series of virtuosic variations. The last is a Tchaikovsky-style waltz in 3/8 meter. The energetic finale follows without pause. Its themes are closely related to those of the first movement, both in rhythm and melodic contour, and give this immense work an unusual sense of formal unity and coherence. After a brief cadenza toward the end, the piano enters (Vivacissimo) with thundering chords triumphantly restating the opening bars of the first movement. The melancholy gloom of the second movement (and of the tonic key of D minor) now conquered, the soloist leads the way to an optimistic, march-like conclusion in D major.

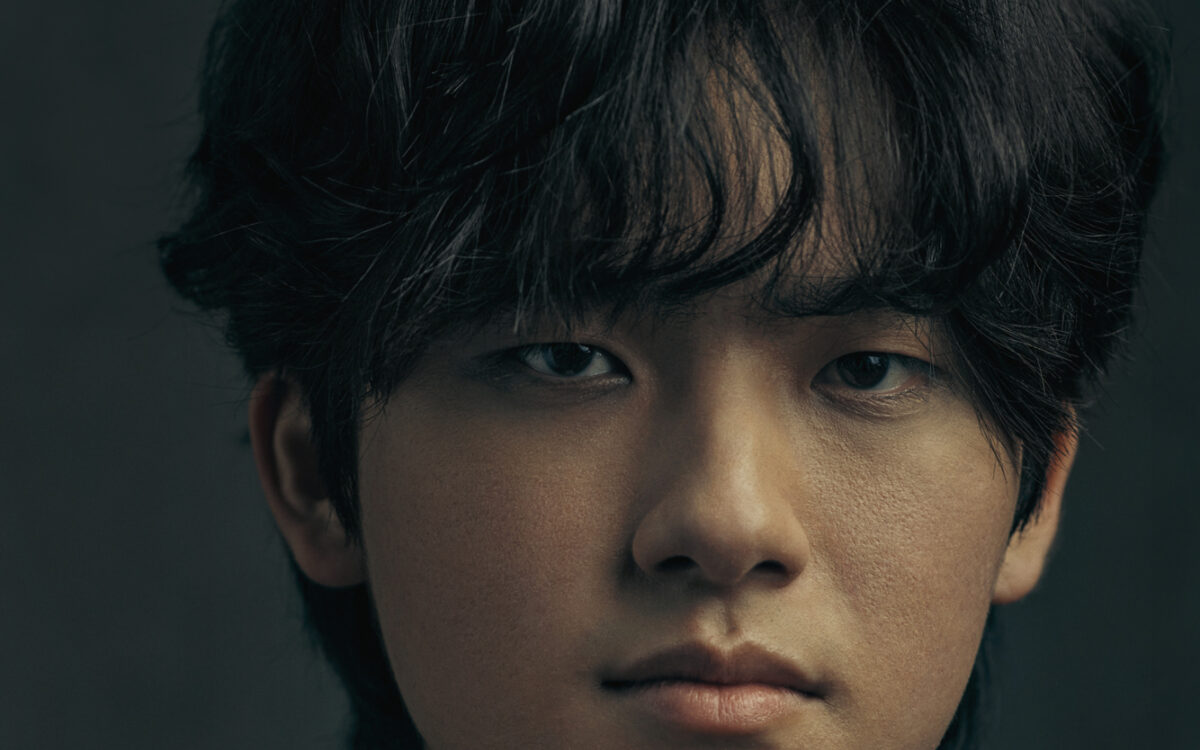

HARLOW ROBINSON

Harlow Robinson is an author, lecturer, and Matthews Distinguished University Professor of History, Emeritus, at Northeastern University. His books include Sergei Prokofiev: A Biography and Russians in Hollywood, Hollywood’s Russians. His essays and reviews have appeared in the Boston Globe, New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Cineaste, and Opera News, and he has written program notes for the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, and Metropolitan Opera.