Piano Concerto No. 1 in C, Opus 15

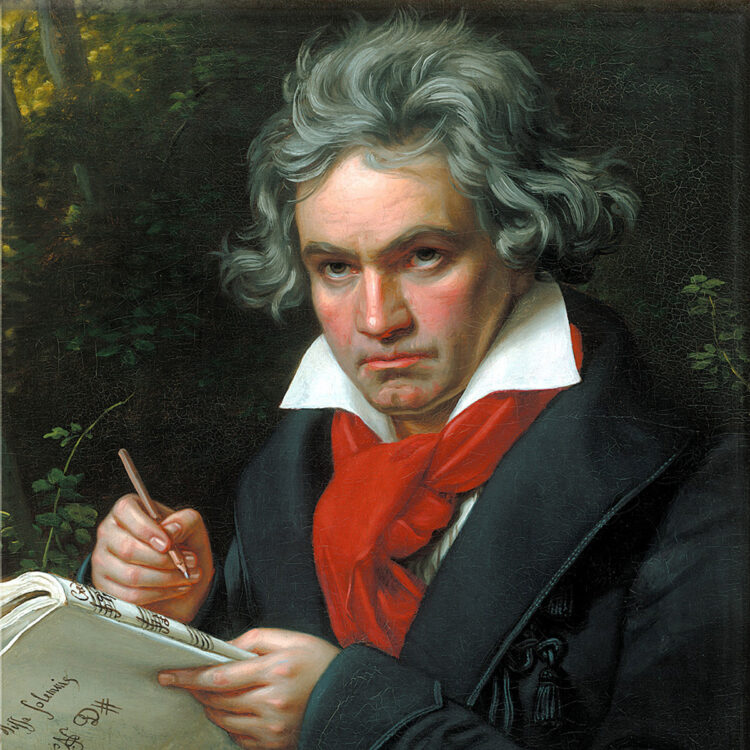

Ludwig van Beethoven was born in Bonn (then an independent electorate) probably on December 16, 1770 (he was baptized on the 17th), and died in Vienna on March 26, 1827.

What we know as Beethoven’s Piano Concerto in C, Opus 15, was sketched in 1795-96, completed in 1798 (three years after the work known as his Piano Concerto No. 2), and probably first performed by Beethoven during his visit that year to Prague. Beethoven himself wrote three different cadenzas for the first movement at a later date, presumably after 1804, judging by the keyboard range required. In addition to the solo piano, the score calls for an orchestra of 1 flute, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings (first and second violins, violas, cellos, and double basses). The Concerto No. 1 is about 38 minutes long.

The Piano Concerto in No. 1 in C, Opus 15, has one foot in the past and the other in the future. Beethoven first put it together around 1795; the final version is from 1800. It was written after the Second Concerto, so numbered because the C major work was published first.

If the opening of the C major concerto shouts some, it does not entirely shout Beethoven. It’s a military march, a familiar mode in concertos of the time. The music begins softly, at a distance, in a stately dah, dit-dit dah figure; with a forte, the parade is upon us. The martial first theme is followed by a lyrically contrasting second. As often in Mozart, the soloist enters not on the main theme but with something new—lyrical, quiet, inward, which alerts us that the agenda of soloist and orchestra are not quite the same. In fact, for all the flamboyant passagework, the soloist never plays the orchestra’s martial first theme. The essential voice of the soloist breaks out above all at the onset of the development, in a suddenly rich, passionate passage.

The second movement commences with a Largo version of the work’s opening rhythmic motto: dah, dit-dit dah. This movement picks up the mood of the middle of the first movement—introspective, gradually passionate. The main theme has a noble simplicity, its piano garlands familiar from 18th-century slow movements, only here not precious and galant so much as atmospheric.

All Beethoven’s concerto finales are rondos (i.e., ABACA…), and rondo finales were usually light, rhythmical, quirky, with lots of teasing accompanying the periodic return of the rondo theme. Beethoven plays that game to the hilt, but pushes it: his rondo theme goes beyond folksy to a rumbustious, floor-shaking dance. For an added fillip, we’re not sure whether the main theme begins on an upbeat or a downbeat, so the metric sense gets amusingly jerked around. The contrasting sections are largely given to brilliant virtuosity. Just before the flashy last cadence there is a brief turn to lyrical and touching. All along that’s been the undercurrent of this concerto that on the surface purports to be more or less conventional, but has an inner life prophetic of much Beethoven to come.

Jan Swafford

Jan Swafford is a prizewinning composer and writer whose most recent book, published in December 2020, is Mozart: The Reign of Love. His other acclaimed books include Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph, Johannes Brahms: A Biography, The Vintage Guide to Classical Music, and Language of the Spirit: An Introduction to Classical Music. He is an alumnus of the Tanglewood Music Center, where he studied composition.

The first American performance of the Concerto No. 1 was given on March 19, 1857, in Cincinnati, by pianist Franz Werner with Frédéric Ritter and the Philharmonic Society.

The first Boston Symphony performance was a single one led by Emil Paur on December 12, 1895, in Cambridge, with pianist Marie Geselschap, after which the orchestra did not play it again until February 1932, with soloist Robert Goldsand under Serge Koussevitzky.