Sinfonietta

Leoš Janáček was born in the village of Hukvaldy, in northern Moravia, in the eastern part of what is now the Czech Republic, on July 3, 1854, and died nearby in Moravská Ostrava, Moravia, on August 12, 1928. Janáček composed the Sinfonietta early in 1926, and it was first performed on June 29, 1926, in the Smetana Hall, Prague, with Václav Talich conducting the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra.

The score of the Sinfonietta calls for 4 flutes and piccolo, 2 oboes and English horn, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, and bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 9 trumpets in C and 3 in F, 2 bass trumpets, 4 trombones, 2 tenor tubas, bass tuba, timpani, bells, cymbals, harp, and strings (first and second violins, violas, cellos, and double basses). Duration of the Sinfonietta is about 22 minutes.

Few composers have revealed such prodigious invention so late in their career and so abundantly as Janáček did in the 1920s. As he approached his seventieth year, his productivity and his energy, far from slowing down, redoubled. His career had developed slowly but surely under the banner of the great Czech national revival spearheaded by Smetana and Dvořák, but he was nearly 50 before he enjoyed any wide success in his homeland. In 1904 the opera Jenůfa was staged in Brno, where Janáček worked as organist and teacher, but it was not until 1916, when he was over 60, that the performance of this same work in Prague catapulted him to international fame. For the remaining twelve years of his life, he composed music at an astonishing rate, having perfected a remarkably individual style and a powerful dramatic sense.

First came three operas in quick succession: Kátya Kabanová, The Cunning Little Vixen, and The Makropulos Affair, interspersed with chamber music, including the First String Quartet and the wind quintet entitled Youth. The operas no longer had to wait years for performance; they were heard at once in Brno and Prague, and Jenůfa was taken up in Berlin and New York also. This upsurge of the creative flame was fueled not only by international success but also by pride in the rebirth of an independent Czechoslovakia after three centuries of Austro-German domination. Janáček felt passionately close to his country and devoted many years of his life to collecting and publishing Czech and Moravian folk music.

A further stimulus to Janáček’s work in these years was a passionate friendship with Kamila Stösslová (1891-1935), a married woman thirty-eight years younger than himself whom he met in 1917. Although she responded with much less ardor, he wrote to her almost every day for ten years and fashioned his operatic heroines on his image of her.

Janáček had composed a handful of symphonic poems (but no symphonies) when he was invited to write an orchestral work by the Sokol gymnastic festival in Prague. He set to work in March 1926 (he was 71 years old) and completed what he called a “nice little sinfonietta with fanfares” within a month. From the beginning he had the sound of military fanfares in his mind, having sat with Kamila Stösslová in a public park one afternoon the previous summer in the town of Písek, listening to a military band. The opening movement of the Sinfonietta, for brass and percussion only, was Janáček’s first thought for the commission, but it quickly expanded into five movements for full orchestra, with the fanfares returning at the end. On several occasions he described the work as his “Military Sinfonietta.”

With the score complete, Janáček left for a visit to London at the invitation of Rosa Newmarch, a vigorous champion of Czech music to whom the Sinfonietta was dedicated. He was received with enthusiasm, and despite the General Strike then gripping England, he was able to make visits and attend concerts. At the London Zoo he noted down the monkeys’ cries, and at his hotel he notated the bellhop’s speech inflections. His next visit was to Berlin for the premiere there of Kátya Kabanová, and he was back in Prague on June 26 for the first performance of the Sinfonietta, given by the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra under Janáček’s stalwart exponent Václav Talich. Before the composer’s death two years later, the work had been given in all the major cities of Germany and Austria, as well as in London and New York.

The Sinfonietta is quite unlike any other orchestral work of its time, or indeed of any time. Most of the melodic ideas bear the strong stamp of Czech folk dance, with short uneven phrases frequently repeated. There are no transitions, no symphonic development, no settled tonality. In its orchestration, the military aspect of the work explains the bass trumpets, the tenor tubas, and the phalanx of normal trumpets, all twelve of which only play together at the last chord. Most striking of all is the virtuoso writing for trombones, especially in the low register, calling for an agility that might have seemed excessive for bassoons or cellos. The timpani are to be tuned to unusually high pitches. The angular writing for the strings is fiendishly awkward but effective, and the woodwinds have to scurry about with extraordinary fleetness.

After the opening fanfares, the second movement is perhaps equivalent to a symphony’s first movement, though without any of the expansiveness that might suggest. For a while the third movement, with its passionately yearning phrases, evokes a contrasting slow movement, but the pace suddenly quickens and a brassy trombone tune sets the winds yelping like a pack of demented dogs.

The fourth movement is more of a character piece, with a tune of obviously folkloric origin stated by three trumpets in unison and repeated many times. It leads to an extraordinary slithering passage and a wild prestissimo ending. The final movement goes from a mood of quiet solace to frantic reiterations of characteristically abrupt phrases, some high skirls in the winds, and a return, subtly prefigured, to the stately fanfares of the opening.

After the Sinfonietta, Janáček went on to compose his Glagolitic Mass, a grand and appropriate coda to a lifetime devoted to writing for chorus, particularly for men’s chorus. In his last year he completed another opera, the stark setting of Dostoyevsky’s From the House of the Dead, and his Second String Quartet. By the end of this dramatic crescendo in his career, his musical language had departed as much from orthodox styles as had that of Stravinsky or Schoenberg or Berg, yet it was never adopted as the basis for modernist developments. Despite its profound roots in folk music, it was always too personal to be imitated, although Janáček’s influence as a teacher was wide and long-lasting. He had never expected his work as a teacher, as an animator of Moravian musical life, or as a folklorist and theorist to be overshadowed by his fame as a composer, and never wanted it to happen, but that was his remarkable fate, and his works will never cease to sound startling and fresh.

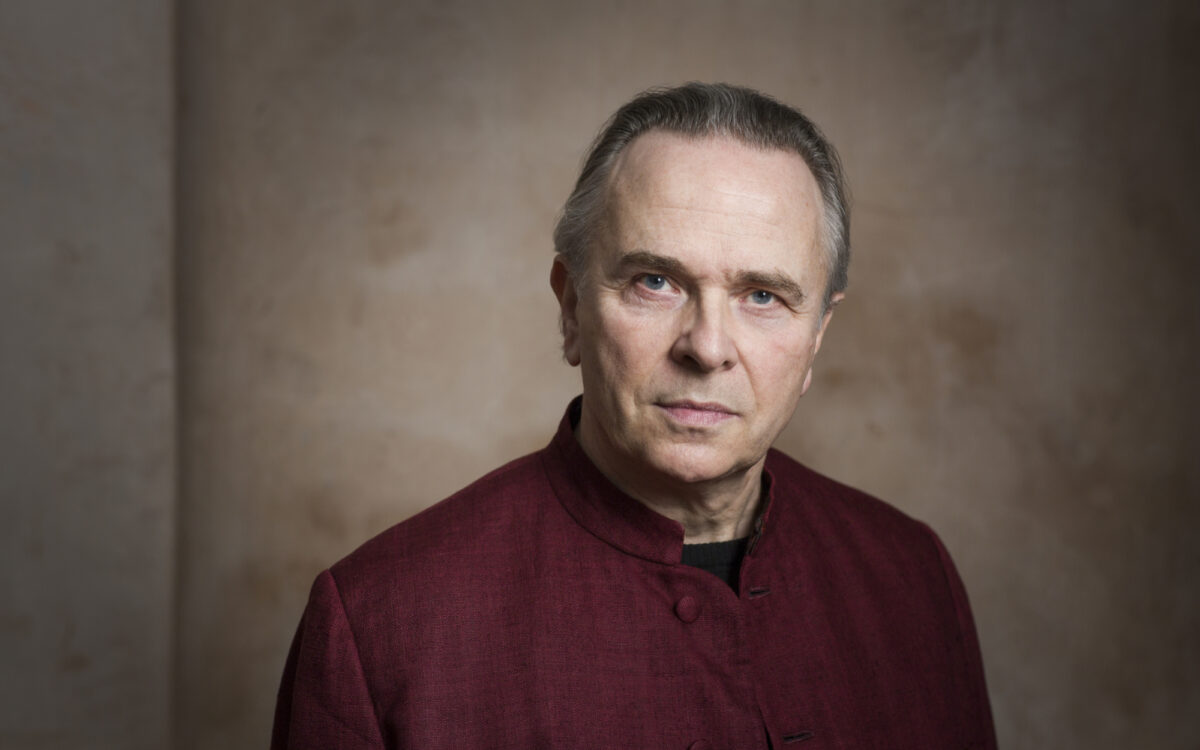

Hugh Macdonald

Hugh Macdonald taught music at the universities of Cambridge and Oxford and was Professor of Music at Glasgow and at Washington University in St Louis. His books include those on Scriabin, Berlioz, Beethoven, and Bizet, and was general editor of the 26-volume New Berlioz Edition. His Saint-Saëns and the Stage was published in 2019 by Cambridge University Press.

The first American performance of Janáček’s Sinfonietta was given by the New York Symphony Society on March 4, 1927, with Otto Klemperer conducting.

The first Boston Symphony performances of the Sinfonietta were given by Erich Leinsdorf in October 1968, in Boston, Brooklyn, and Providence.