Coltrane: A Centennial Symphonic Celebration

Coltrane: A Centennial Symphonic Celebration curated by Carlos Simon & Coltrane Estate

John William Coltrane was born September 23, 1926, in Hamlet, North Carolina, and died in Huntington, New York, July 17, 1967. The original recordings chosen by Carlos Simon and orchestrated for this program were all recorded between spring 1957 and the end of 1964. The present arrangements were made specially for this project, which has previously been presented in Toronto and in London and which is a co-commission of TO Live and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. Presented in cooperation with Polyarts.

John Coltrane: A Force for Good

by Emmett G. Price III, Ph.D.

Coltrane’s thorough understanding of the roles and functions of music in Black American Culture led him to pursue an incredible legacy of practice, rigorous study, self-realization, spiritual awakening, and creative expression that touched listeners worldwide.

—Leonard L. Brown“As a Boston jazz radio show host for over three decades, I might say that Coltrane’s music must be played simply because it’s beautiful music that must be heard.”

—Eric D. Jackson

[Quotes from Leonard L. Brown, John Coltrane & Black America’s Quest for Freedom: Spirituality and the Music (Oxford University Press, 2010), 31, 180.]

In 1965 John Coltrane played the Newport Jazz Festival (July 2-4) and then came to Boston for a residency at the Jazz Workshop (July 7-11) with his classic quartet featuring McCoy Tyner (piano), Elvin Jones (drums), and Jimmy Garrison (bass). The musical polymath was at the height of his career as demonstrated on the July 11, 1965, recording later broadcast on WGBH Radio.

A fan of Lester Young and Johnny Hodges, an apprentice of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, a protégé of Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk, Coltrane is remembered for his technical mastery of the tenor and soprano saxophones, his prodigious work ethic, and his superior endurance while improvising. He is remembered for his endless creativity, courageous melodic and harmonic inventions, and his one-of-a-kind performance practice. As one of the most respected and revered creative artists of the 20th century, Coltrane dedicated his life to the service of others as a cultural griot, spiritual mystic, compassionate humanitarian, and Black liberation activist. Coltrane was also one of this nation’s great composers, with over 70 works, including eight on tonight’s program. Brilliantly curated by the inaugural Deborah and Philip Edmundson Composer Chair, Dr. Carlos Simon, the programming of Coltrane’s greatest hits with the Boston Symphony Orchestra is historic, timely and a clear validation of Coltrane’s prowess as a composer.

As a self-described Coltrane scholar (my first published academic article was on Coltrane over 30 years ago) and as a member of Boston’s Jazz Community (over 20 years), I am excited to hear, see, feel, and experience John Coltrane in the historic Symphony Hall as played by the Boston Symphony Orchestra. And yet, I continue to ponder what this means. Coltrane has never been honored with the designation “Great American Composer.”

Coltrane was a contemporary of the significant Black composers Julia Perry (1924-1979), Hale Smith (1925-2009), and Thomas Jefferson “T.J.” Anderson (b.1928). There is no documented record of Coltrane meeting either Perry, a 2-time Guggenheim Fellow (1954 & 1956), Tanglewood Fellow, and American Academy of Arts and Letters Prize awardee (1964) or Smith, who worked with Eric Dolphy, Ahmad Jamal, Oliver Nelson, Melba Liston, Randy Weston, and Dizzy Gillespie as pianist and arranger. However, Coltrane and Anderson did know one another during the early 1960s, as the Tufts University Austin Fletcher Professor of Music Emeritus shared in a 2006 conversation. In fact, it is probable and very likely that Dr. Anderson’s staunch advocacy and activism through essays and opinion pieces during his tenure at Tufts (1972-1990) and his connections to BSO musicians served as one of many catalysts for a dynamic shift in the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s commitment to expanded programming of the past few decades, as is evident in recent tributes to Duke Ellington and Wayne Shorter and in Carlos Simon’s newly created role.

Coltrane was born in Hamlet, North Carolina, in 1926 under the shadow of Jim Crow segregation laws. Economic hardship, racial tensions, and the death of significant family members, including Coltrane’s father and both grandfathers, served as stimuli for the family’s move to Philadelphia in 1938. As part of a religious family where both of his grandfathers served as African Methodist Episcopal Zion ministers, Coltrane maintained an interest in religion, faith, and spirituality that would heighten after a spiritual awakening in 1957. This manifested that year in his intentional exodus from a life plagued by narcotics and excessive drinking and the introduction of a new sound that elevated his stature as a standout musician. Described by many as equally mellifluous and divine, Coltrane’s sound was greatly driven by his compositional acumen, whether notated or explored through improvisation.

Coltrane’s compositions and improvisations were always both fiercely compassionate and deeply contemplative. He was in many ways a “musician’s musician,” part tactical coach, part wellness counselor, and part spiritual guru. His musical output, a reflection of his inner work, was and remains global, never nationalistic; it stands as both spiritually guided and yet never bound by the constraints of religion. It is human-centric, with a message to inspire humanity to its best even while enduring its worst. Coltrane remains a universal force akin to his contemporaries Malcolm X (1925-1965) and Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929-1968), both of whom he admired. By 1964, when Coltrane acknowledged a second spiritual awakening, his convictions further intensified, leaving him somewhat distanced from fans unable or unwilling to imagine the world Coltrane was aiming to manifest, a world of deep interconnectedness, devoid of fear, and beholden to a divine and cosmic call towards, love, justice, and peace. For these reasons and countless others, it is difficult to limit Coltrane to even such a designation as Great American Composer—because for so many, he is and will always be so much more.

Almost 60 years after his death at the age of 40, and 50 years since his well-remembered residency in Boston, we celebrate Coltrane, his musicianship, his compositions, and his dynamic legacy. Tonight’s repertoire is overflowing with Coltrane classics both composed by him and composed by others and created anew through his performances.

Blue Train (arr. Erik Jekabson)

While playing almost nightly with Monk, Coltrane took his own band to the Van Gelder Studio to record his only Blue Note album. The Blue Train album featured Lee Morgan (trumpet), Curtis Fuller (trombone), Kenny Drew (piano), Paul Chambers (bass), and “Philly” Joe Jones (drums), and displayed Coltrane’s new musical concepts and the evolving “sheets of sound” that would come to fruition in Giant Steps. The title track, Blue Train, reveals Coltrane’s unyielding grounding in the blues and would soon emerge as a new jazz standard.

Naima (arr. Andy Milne)

From the Giant Steps album, Naima is a lyrical ballad dedicated to Coltrane’s first wife, Juanita Naima (Grubbs) Coltrane, an important source of strength in his life. Coltrane composed this gorgeous tune with lush harmonic movement and a deep and emotive feel. Coltrane’s playing on this song offers yet another example of his methodical and deep connection with the saxophone, availing the horn to be truly an extension of his own human voice.

Crepuscule with Nellie (arr. Andy Milne)

In spring 1957, after Coltrane had been dismissed from Miles Davis’s band, Thelonious Monk invited him to join his group. He played with Monk through the end of the year, rejoining Davis in 1958. Monk wrote Crepuscule with Nellie for his wife Nellie, who was having medical challenges at the time. Monk took the band into the recording studio on June 26, 1957, to record the Monk’s Music album; a later live version was recorded on November 29, 1957, at Carnegie Hall with the Thelonious Monk Quartet, including Coltrane. That recording was rediscovered and released in 2005, revealing both Monk and Trane at pivotal moments in their individual and shared musical journeys, and features one of the greatest recordings of this tune.

Giant Steps (arr. Steven Feifke)

Composed and recorded while he was in the Miles Davis sextet, the titular track of Coltrane’s album Giant Steps is one of the most notable jazz standards of all time. This piece spotlights Coltrane’s compositional sophistication with the uncommon yet alluring movement of the bass line by complex “giant steps,” which serve as the basis for what have come to be known as “Coltrane Changes” in the colloquial nomenclature of musiciansacross genres and generations. Riding the changes (chord progression), Coltrane’s virtuosic playing is strong, full of musical ideas, and thick with uncommon sonorities that DownBeat magazine critic Ira Gitler dubbed “sheets of sound.” Coltrane’s rising stature as an influential leader among musicians and composers is strongly established with this work.

My One and Only Love (arr. Ben Morris)

Following the success of the Duke Ellington & John Coltrane album, Impulse! Records producer Bob Thiele envisioned a Coltrane project with leading jazz vocalist Johnny Hartman that was recorded in March 1963 with Coltrane’s classic quartet. Hartman’s rich and velvety baritone voice paired nicely with Coltrane’s potent yet sensitive accompaniment on Guy Wood’s and lyricist Robert Mellin’s now-classic song “My One and Only Love.” The Coltrane and Hartman version remains one of the most beloved versions of the tune originally made famous by Frank Sinatra in 1953. John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman was Coltrane’s only album in collaboration with a vocalist.

So What (arr. Tim Davies)

When Coltrane returned to the Miles Davis band in 1958, the sextet pushed the envelope in jazz. By spring 1959 the band was in the studio recording the now legendary album Kind of Blue, featuring Davis (trumpet), Coltrane (tenor saxophone), Julian “Cannonball” Adderley (alto saxophone), Bill Evans (piano), Paul Chambers (bass), and Jimmy Cobb (drums). (Wynton Kelly was pianist on the track Freddie Freeloader.) The lead track, So What, signaled a new modal approach to composing and improvising that later inspired Coltrane’s Impressions and other works. Of note, Adderley did not perform on So What, leaving Coltrane even more room to stretch out on his solo.

Blue in Green (arr. Cassie Kinoshi)

Composed by Bill Evans and credited to Davis, Blue in Green is an introspective ballad from the Kind of Blue session, guided by an unresolving cyclical harmonic progression. Often known for his precise and up-paced playing, Coltrane plays a short solo on this historic recording that is notable in its contemplative, emotionally transparent approach.

A Love Supreme: Acknowledgement (arr. Andy Milne)

One of Coltrane’s most noted compositions and performances, A Love Supreme, Part I: Acknowledgment features Coltrane’s developing approach to emphasizing short motifs, in this case four-note motifs. “Acknowledgement” serves as the opening to a four-part suite offering testimony to Coltrane’s second spiritual awakening, through which he came to understand that the divine imparted to him a new message and a new way of spreading that message. The Love Supreme album, released in 1965, signaled a radical shift in the music world, especially in jazz.

In a Sentimental Mood (arr. Carlos Simon)

In September 1962, Impulse! Records producer Bob Thiele brought jazz elder statesman Duke Ellington and rising star John Coltrane together for a recording project, released as Duke Ellington & John Coltrane in 1963. Ellington’s classic ballad In a Sentimental Mood was a highlight of the session and the album. Their interpretation of Ellington’s 1935 composition features the sophistication and elegance of Ellington and his bass player, Aaron Bell, matched with the warm and robust sound of Coltrane and his drummer Elvin Jones.

Crescent (arr. Ben Morris)

As Coltrane continued to mature as a musician and composer, his evolving sound elevated his focus on spirituality to the place where he remarked that playing the saxophone was akin to prayer. In his playing and compositions, one could discern a deepened sense of contemplation and meditation and a unique approach to sound derived from his study of traditional music from India and parts of Africa. The title track on his 1964 album Crescent offers one glimpse into this new compositional approach and performance practice.

Central Park West (arr. Tim Davies)

Recorded as part of the My Favorite Things session in 1960, Coltrane’s pensive Central Park West features soprano saxophone, which Coltrane began exploring around this time. Although recorded in 1960, the track was not released until 1964.

Alabama (arr. Carlos Simon)

One of Coltrane’s most potent compositions, Alabama is a musical elegy in honor of Addie Mae Collins (14), Carol Denise McNair (11), Carole Robertson (14), and Cynthia Wesley (14), four Black girls killed in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, on September 15, 1963, by the Ku Klux Klan. The Sunday morning act of violence was a significant precursor to increased activation within the Civil Rights Movement. Coltrane composed Alabama inspired by the phrasing of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s eulogy for the deceased. Part meditation, part protest song, and part call to action, Alabama remains a testament to Coltrane’s active engagement in the Black liberation movement.

Impressions (arr. Ben Morris)

Although recorded in 1961, Coltrane’s Impressions was released in 1963 and quickly emerged as one of the important albums featuring the classic quartet of Coltrane, McCoy Tyner (piano), Elvin Jones (drums), and Jimmy Garrison (bass). Inspired by Coltrane’s work with Davis during the Kind of Blue recording, Impressions reveals Coltrane’s investment in and development of the use of modes within his compositional technique and in improvisation. Impressions quickly became a beloved jazz standard.

My Favorite Things (arr. Jonathan Bingham)

In 1959, Richard Rodgers’s & Oscar Hammerstein II’s The Sound of Music debuted on Broadway. Coltrane heard “My Favorite Things,” one of the show’s headline hits, in late 1959 or early 1960 as he was further developing his modal improvisational techniques. His justly celebrated 1960 recording of the song explores the sound of the soprano saxophone and incorporates some of the global music and techniques he was now actively studying. When it was released in spring 1961, the title track emerged as his first commercial hit.

Although not performed on these concerts, one further work from Coltrane’s later recordings should be mentioned as an illustration of the composer’s evolving spiritualism and humanity. Devastated by the Vietnam War, reflective of the atomic bombings in Japan at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and experiencing the turmoil of the Black liberation movement in the United States, Coltrane composed his Peace on Earth as a liturgical requiem that codified his life’s message in the most timely and relevant way possible.

In 1969, the Saint John Coltrane African Orthodox Church was founded in San Francisco, California, canonizing Coltrane for his transcendent and divine contribution to the world through his compositions, his prose, and his powerful witness. In 2007 Coltrane was posthumously awarded a special citation from the Pulitzer Board for his work as a composer, improviser, musician, and central figure in the narrative of jazz.

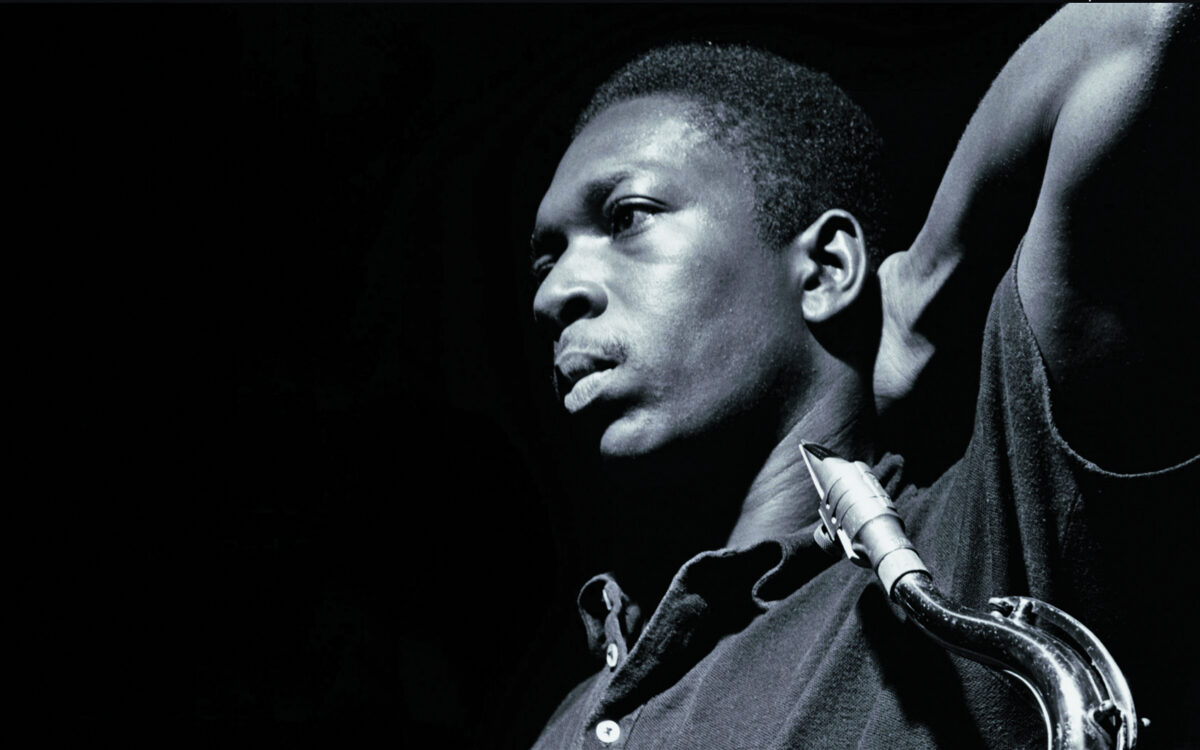

As a way of deepening our experience with Coltrane’s compositions, influences, and legacy, the John Coltrane Estate has provided a rich array of Coltrane images, some rarely before seen. May we embrace this music, and in doing so remember the creative human being who shared it with us.

To me, you know, I feel I want to be a force for good.

—John W. Coltrane[Quote from Frank Kofsky, Black Nationalism and Revolution in Music (Pathfinder Press, 1970): 241.]

Emmett G. Price III, Ph.D.

Emmett G. Price III, Ph.D. is founding Dean of Africana Studies at Berklee College of Music and Boston Conservatory at Berklee. He is a Trustee of the Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston and the Chair of the Board of Trustees for the Boston Landmarks Orchestra.