Triple Concerto for Violin, Cello, and Piano in C major, Op. 56

Composition and premiere: Beethoven began the Triple Concerto in 1803 and wrote it over the following year, publishing it in 1804. The concerto may have been performed that year at the home of Beethoven’s friend and patron Archduke Rudolph, for whom the piano part was reported to have been written, but there is no record of such a performance. The public premiere took place in Leipzig in April 1808.

First BSO performance: January 21, 1882, with Georg Henschel, conductor and pianist, Terese Liebe, violin, and Theodore Liebe, cello. First Tanglewood performance: July 25, 1965, Seiji Ozawa conducting; Eugene Istomin, piano; Isaac Stern, violin; Leonard Rose, piano.

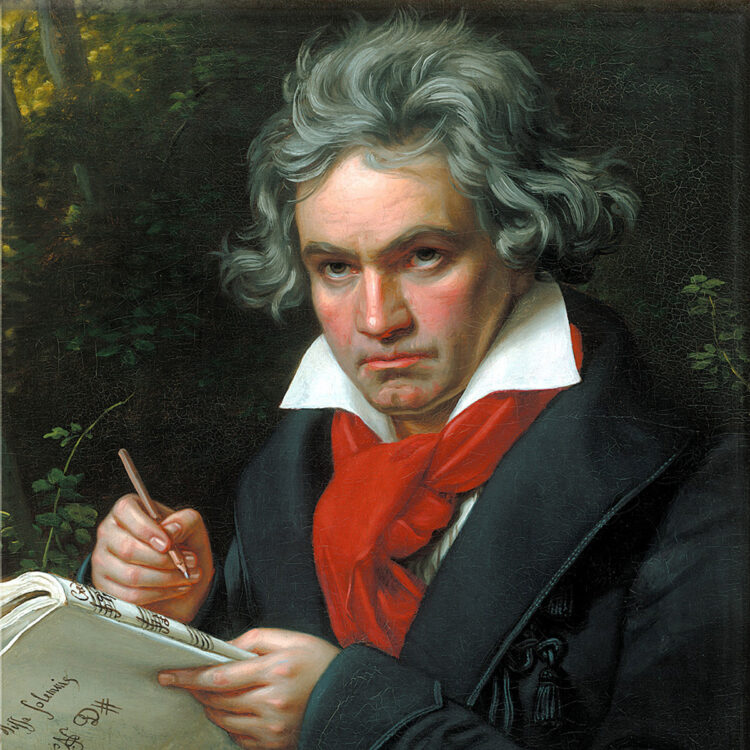

Beethoven composed his Triple Concerto, Opus 56, for his pupil and patron, the Archduke Rudolph of Austria, who was a pianist and amateur composer. The concerto was intended for performance by the Archduke himself, along with his court violinist and cellist, for which reason Beethoven made the piano part much easier than those of the two string soloists. He sketched the first movement early in 1803, about the same time he was composing the Eroica Symphony (which was largely finished by November), and continued working on it the following year, while also planning and writing two of his most famous piano sonatas—the Waldstein and the Appassionata—and the first of the Razumovsky quartets. Thus the Triple Concerto falls squarely into the period of Beethoven’s most prolific, and popular, work.

The choice of three soloists for his C major concerto was an unusual one. Not that there weren’t concertos with more than one soloist before; the Baroque era is full of them, and even the symphonie concertante of the classical era has many examples. But the particular combination of piano, violin, and cello seems never to have been tried before. The choice of solo instruments may have been dictated by his dedicatee, the young Archduke Rudolph, who wanted it for performance by his private orchestra. He was one of the Emperor’s sons, was no mean pianist himself (he was a pupil of Beethoven’s), and remained for years one of the composer’s most steadfast supporters. The Archduke himself was to play the piano in the performance, and the violin and cello parts were written for the principal players in the orchestra, a violinist named Seidler and the cellist Anton Kraft, who was one of the leading virtuosos of the day. Beethoven apparently admired Kraft especially, because the cello part is notably more difficult than either of the other two solo parts and remains, indeed, one of the hardest works in the cello repertory.

It is not entirely clear when Beethoven finished the concerto. He interrupted work on it in January 1804 to begin the composition of the opera Leonore (which ultimately became Fidelio). In the spring of 1804 he spent some time getting the score of the Eroica into its final state for performance. And he seems to have been shifting back and forth between several works in progress at this time, so it may have been a year or more before he actually completed the piece, probably at the urgent request of the Archduke. The Archduke presumably kept the manuscript (now lost) of the finished work and took part in private performances. The parts were published in 1807—oddly enough with a dedication to Prince Lobkowitz rather than the Archduke—and the work was publicly performed in Vienna’s Augarten in May 1808.

Like many of the post-Eroica works, the Triple Concerto is expansive, making a virtue out of length. In this particular case the length is generated in part by the presence of three soloists, each of whom requires a separate statement of the material in the exposition. This format, in turn, means that the concerto as a whole tends more toward lyric elaboration than to dramatic transformation of the material. The first movement is far more leisurely and less heaven-storming than Beethoven’s other compositions of the same time, reveling instead in the genial interplay of sonorities, and grows out of the very opening hushed gesture of the orchestral cellos. (It is interesting to note that while Beethoven often liked to start his symphonies with a loud chord, he tended in most cases to begin concertos softly, even mysteriously.)

To follow the unusually long first movement Beethoven employed the same procedure he had already tried in the Waldstein Sonata of having a short set of variations that links directly to the final Rondo alla Polacca, which uses the polonaise rhythm that even then, long before Chopin, was popular all over Europe for festive music of a particularly ceremonial type in triple meter.

The Triple Concerto has long been the stepchild of Beethoven’s concerto compositions, the work least often played and most severely criticized. To be sure, the presence of three soloists sometimes leads to more repetition than we expect from Beethoven, but at the same time the sheer breadth of the work and the intrinsic beauty of many of the ideas mark it as a fascinating step in Beethoven’s progression. And beyond the Triple Concerto, we can already sense the two broadly lyrical concertos—the Violin Concerto and the Fourth Piano Concerto—that could not have been written without this preliminary.

STEVEN LEDBETTER

Steven Ledbetter, a freelance writer and lecturer on music, was program annotator of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1979 to 1998.