Bernstein at Tanglewood: A Love Letter

Tanglewood is verdant in the summer. Lushness pours out of every crevice and crack, inviting visitors to luxuriate in the heavy summer air, a glass of something in their hand. For musicians — the students who devote themselves to perfecting their craft, and the professionals who are there to advance their art — it is a heady, infectious feeling of potential; there is magic to be made in the music. Perhaps that’s what kept Leonard Bernstein coming back, nearly every summer from 1940 right up to his passing in 1990.

“Tanglewood was completely in his DNA,” said BSO bassist Todd Seeber, who was a Tanglewood Fellow in 1983 and ‘84, and joined the BSO in 1988. “Tanglewood was everything that was important to him.”

Bernstein’s devotion to Tanglewood, and particularly to the Tanglewood Music Center and its students, was one of the transcendent loves of his life. Here, in their own words, BSO musicians who worked with Leonard Bernstein at TMC and the BSO over the years remember him.

Principal bass Edwin Barker, TMC Fellow 1975, joined the BSO in 1976: I had no idea what orchestra music was when I was a young child. But I remember seeing the Young People’s Concerts on our little black and white TV when I was 5 or 6 years old, and there he was, waving his arms around. I said to my mother, “Why is that guy waving his arms around?” I thought it must be that when he raises his arm high, the musicians play high notes, and when his arms are low, they play low notes. For a lot of people of my generation, those broadcasts were our first exposure to orchestras.

Assistant principal bass Lawrence Wolfe, TMC Fellow 1966-1969, joined the BSO 1970: I was a young bass player when Leonard Bernstein did his televised youth concerts. He had on a cello player named Yo-Yo Ma. He had on a bass player named Gary Karr, and I saw that and thought, “Oh my god, that’s what a bass can do.” So, I practiced harder and harder and harder. Years later I was at Boston University and Gary Karr came to New England Conservatory, and I transferred to NEC to study with Karr. That’s how deep Lenny goes for me.

Violinist Tatiana Dimitriades, joined in 1987: I had a very predisposed opinion of what I thought he was going to be like. I thought he was going to be a showman who was stoned out of his mind and crude. And I was very much feeling the opposite after playing with him. He was a showman, but it was all in pursuit of honoring the composer’s wishes. He just threw himself into the music like no one else. He lived and breathed for music.

Violinist Jennie Shames, joined in 1980: He was always iconic to me, but I would say I honestly wasn’t prepared for his intensity and charisma. He would walk into a room and take up all the oxygen. That was a presence I had never been in front of before.

Violinist James Cooke, joined in 1987: I had no idea what to expect. The grand entrance he made a couple minutes after rehearsal began … it seemed like he was greeting and hugging half the orchestra.

Seeber: He would walk onstage and have his arms around half a dozen people within a couple of minutes. Planting kisses on everyone. In nutshell, frankly, he was everything I was led to believe he was going to be. He was incredibly gregarious. He loved people. He never failed to bring a room alive. He was the life of any party. And there were several parties.

Barker: He went way back with a lot of the players, so when he would first come back to Tanglewood after having been away from us for a year or so, at the first rehearsal there would be a lot of kissing and hugging for the first 20 minutes of rehearsal.

My wife Pam and I were both Tanglewood Fellows in 1975. The intensity of the Tanglewood Fellowship Program has a way of fostering long-term relationships. Pam and I have been married for 44 years now.

That summer, the Fellowship Orchestra performed the Ravel Piano Concerto with Bernstein playing and conducting from the piano. The piece has a prominent and exposed horn solo that Pam performed. I remember after the performance during the applause — you know Bernstein loved to go up and kiss people — Bernstein went up to her and gave her a well-deserved smooch! Well-deserved, even it wasn’t from me!

Violinst Sheila Fiekowsky, joined in 1975: His smile could light up a room. He really loved to talk and kiss everyone in the front and tell stories. The rehearsals were chaotic, and he always wanted overtime because there was never enough time for him to talk. And he would throw tantrums. We should have been playing and he just wanted to talk. He wasted time and he would get mad if the rehearsal ended and he wasn’t done talking, he would throw the score on the floor. And he was always smoking, smoking, smoking.

But when he picked up the baton, it was like electricity went through everyone and everybody was just on top of their game. On. Top. Of. Their. Game.

Wolfe: I still remember at Tanglewood, he’d have his scores and several personal aides. One person would light the cigarette, another would pour his glass of water, another would put the scores on the stand, and he’d walk on stage smoking a cigarette. Then he would be asked to put out the cigarette, and he would; it was all for show.

There was one time when the violin part didn’t match what was in his score. He took the score and slammed it on the stage and stomped off stage. At which point his crew — I think he had three people attending to him — they hovered around him and protected and soothed him until the problem was solved. Maybe we took an early intermission, so that all could be made well. Ultimately, we were better for it.

Seeber: He demanded a lot. You’d rehearse and rehearse and rehearse and then all of a sudden, the performance was on another level.

Barker: He burned the candle at both ends. He tended to make his own rules. And he pushed the envelope. He liked to smoke a lot. At Symphony Hall we did a piece of his one time — he was not conducting, he was just there as composer, Seiji [Ozawa, BSO Music Director from 1973-2002] was conducting — and Bernstein, sitting in one of the chairs in the audience, lit up a cigarette. Members of the orchestra noticed, then Seiji noticed and said, “Lenny you’re not allowed to smoke in the hall.” He put the cigarette out and five minutes later he lit up another cigarette. He made his own rules! That’s probably why he was as great as he was.

Bernstein takes a bow, circa 1950

Leonard Bernstein conducting a TMC orchestra rehearsal, ca. 1955

Bernstein coaches a TMC conducting student, ca. 1974

Bernstein conducting from the piano in rehearsal with the BSO, ca. 1975

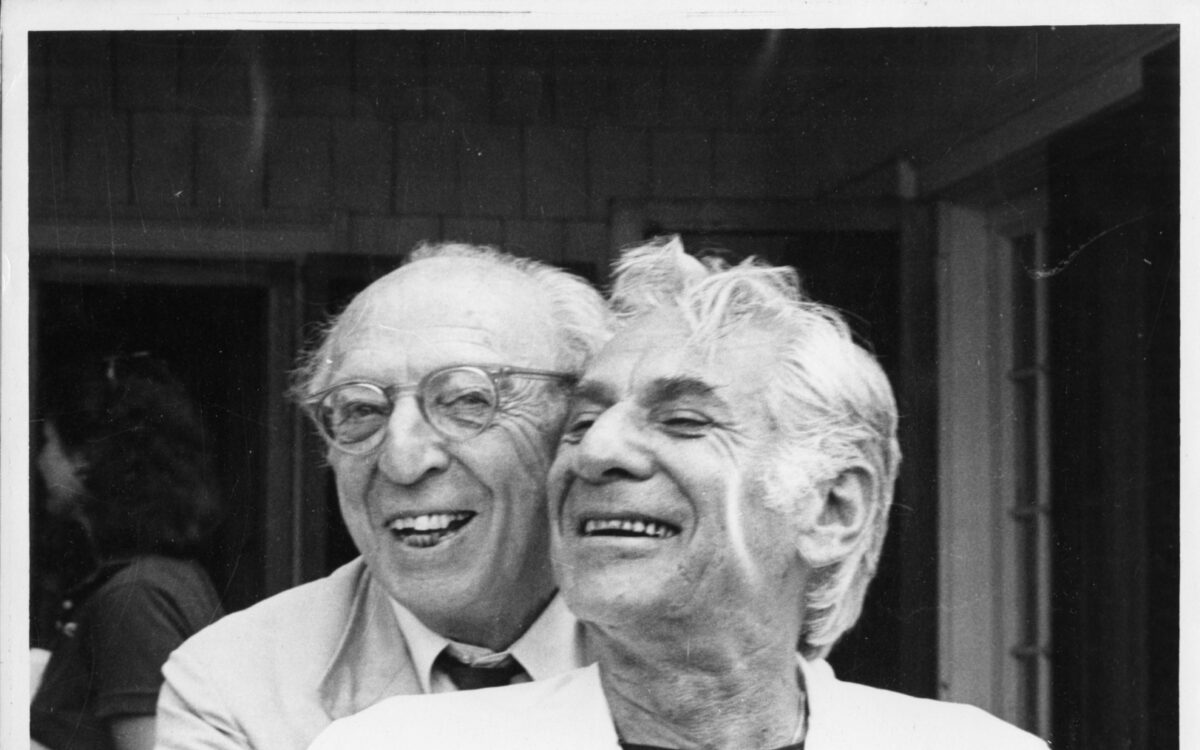

Aaron Copland embraces Leonard Bernstein during the BSO's celebration of Copland 80th birthday at Tanglewood, 1980

Midori performs Bernstein's Serenade (after Plato's Symposium) with the BSO under Leonard Bernstein, 26 July 1986

Leonard Bernstein kneels before performers from the "Bernstein at 70" concert, August 25, 1988

Bernstein leading the BSO, ca. 1989

Bernstein leaves the stage after his last concert at Tanglewood, August 19, 1990

Shames: There was a 1986 concert. We played Tchaikovsky’s Sixth [Symphony], and after there would always be a party a Koussevitzky’s home. We decided to go just to see if we could say hello to Lenny. He came late, and we sat down in the piano room, and we started to talk, and next thing we knew the sun was coming up. We had talked all night.

We talked about everything, a lot of it political. I asked about all the placed he conducted, and his Judaism that was so important to him, and I wanted to know how he conducted in places that weren’t so friendly. And he said, “If I’m not there, I can’t do anything.”

It was just a night of really getting to know him. It was a magical night and not a night you get very often.

Seeber: He really loved connecting with students. I remember standing outside Miss Hall’s School [in Lenox, MA] at a TMC party with a group of students, and he was looking up at the stars, and he said, “You know I’ve had a star named after me.” It was something of an eye-roll, like, “I can’t believe they did that.”

Wolfe: He had this huge Mercedes convertible with license plate MAESTRO1, and to the dismay of the Tanglewood grounds crew, he just drove on to the grounds, wherever and whenever he wanted. Why? Because he’s Lenny.

Shames: When Bernstein conducted, there wasn’t a question of if it was the right or wrong way, it was the inevitable way. It almost felt like he knew the composers. You almost believed it was exactly as the composer wanted it. He would pace things in a way that just came together, and you couldn’t imagine it another way except the way he was doing it. It’s hard to describe. I think I’ve seen maybe five conductors who’ve done that, and none as much as Bernstein. I wish my younger colleagues could have seen the greatness of Lenny. There was nothing else like it.

Fiekowsky: He was incredible. It was just his way. He just embodied the music to such an incredible extent. The way he did it — sometimes his tempos were really slow, but then it convinced you. He would draw a long line. Especially for a kid in their 20s, it was inspiring.

He didn’t beat time. He beat phrases. Those are the best conductors. Andris [Nelsons, current BSO music director] is the same way; he beats phrasing.

Dimitriades: My first summer [at TMC] in 1988, we played Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony. I had played it in high school and college orchestras, but not professionally, and he just blew me away. The next summer was even more amazing. We did Shostakovich Five [Fifth Symphony]. I had never played the piece before; I hardly knew it. But my jaw was practically on the floor watching him take the piece apart. To this day there a moment in the slow movement where I just get goosebumps remembering how he did the timing of it.

Seeber: Emotional isn’t the right word. He was always getting to the heart of what the composer was trying to say. It was very important to him. As important as execution was, the root of it all was the expression. He never ever lost sight of that. That was one of the things that made these performances so transcendent, he never lost site of the tension and pacing of a piece.

Shames: [Music] took over everything about him. He himself was so overwhelmed by the beauty of music, especially when he did something like Mahler. He was more than a consummate musician. He seemed almost not of this world, like he knew something that all of us didn’t know. In the end, that’s who he was; he was a teacher.

Seeber: He always had a very intense symbiosis with an orchestra. He spoke about music to everyone — musicians and non-musicians — more effectively than anyone I’ve ever known. He really loved connecting with students and people. There was never any aloofness. He really, really loved that human connection and that side of music making.

Cooke: It’s hard to convey the extent of his personal charisma. It’s hard to put a factor on that.

His tempos were expansive. You’d hear people complain, “why is he so slow on this.” But the charisma came in when he was conducting. It was obvious that his commitment was complete. And the orchestra, even if they disparaged it, they all went with what he was doing.

There are people you’ve met who were both fully gifted in terms of their intellect and charismatic at the same time. It’s a powerful combination. I don’t think I’ve met anyone who had the same combination.

Shames: For my colleagues and I who worked with Bernstein, I don’t know one of us who wouldn’t say he wasn’t our favorite conductor we’ve worked with. He wasn’t aways the easiest, but he was the most life changing. I miss him every day.

Wolfe: He was just an incredible presence. He walked on stage, and just raw emotion emanated from the very core of his being. It was breathtaking. There was and there will be no one like Lenny.

Maya Shwayder is the BSO's Senior Contributing Editor and Copywriter.