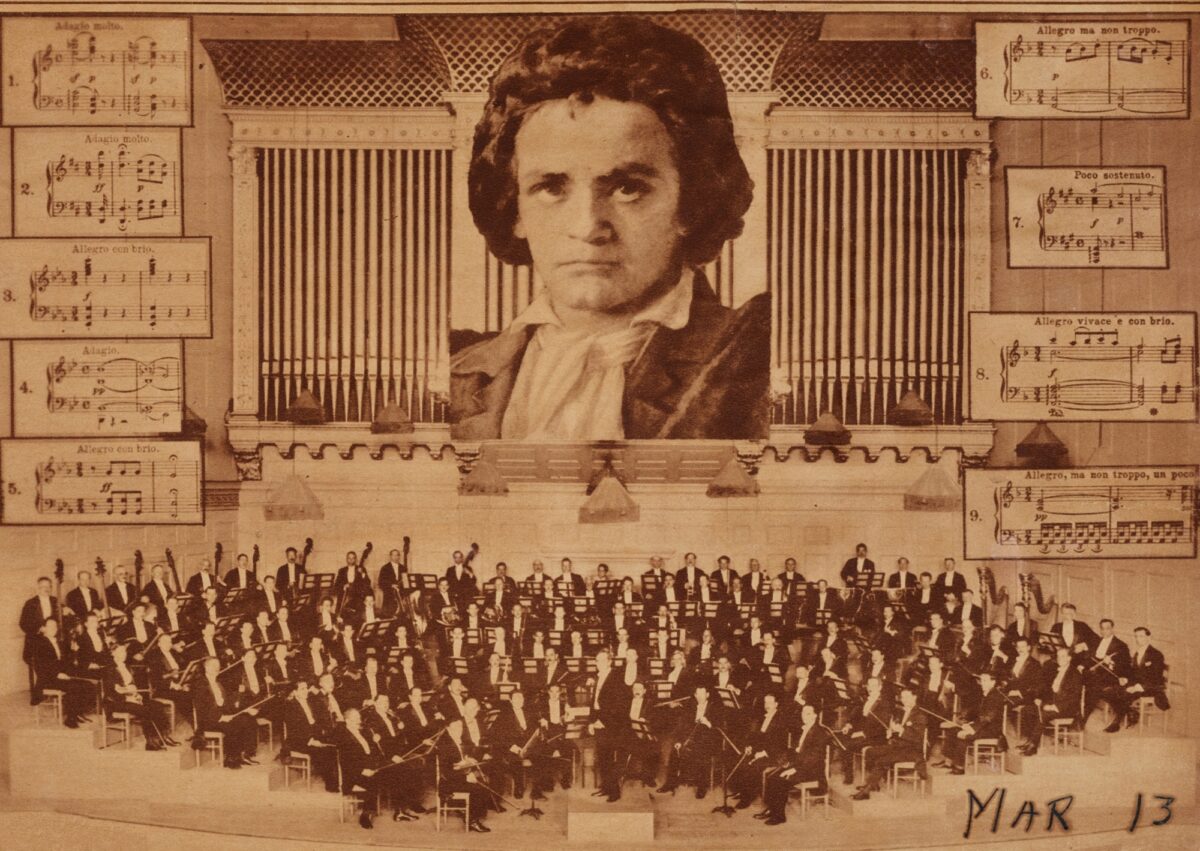

Beethoven's Boldness: The Stories Behind His Second and Third Symphonies

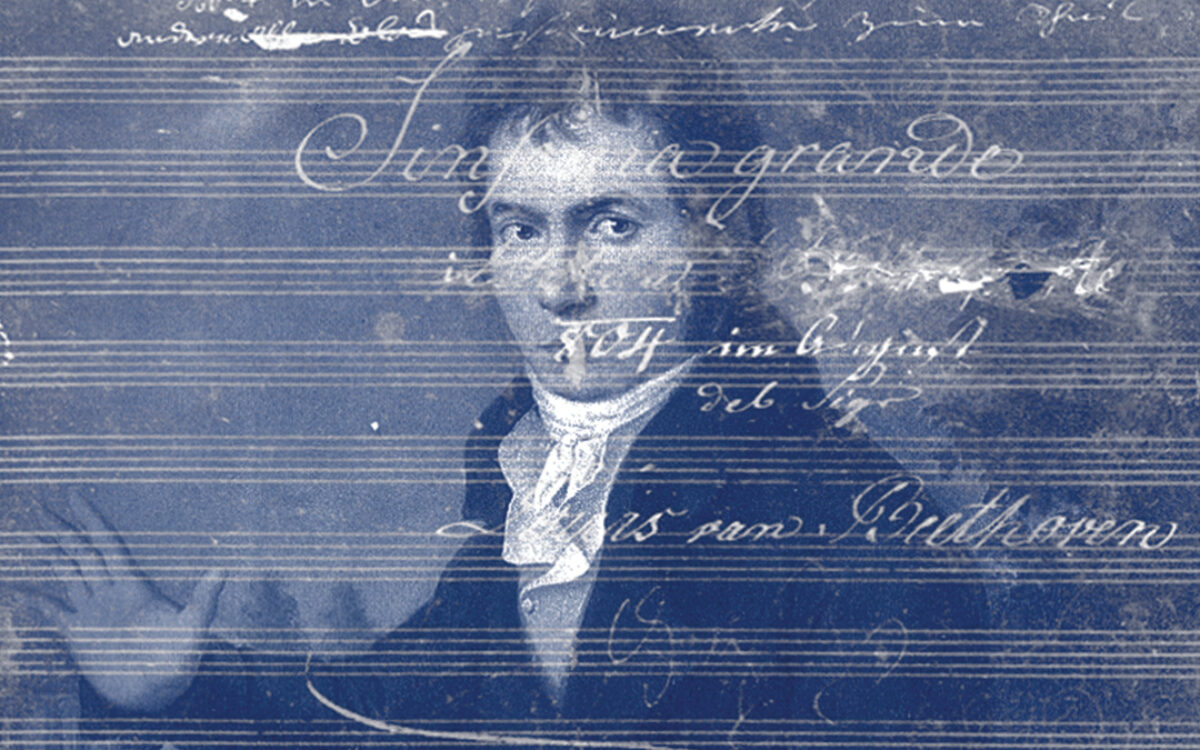

Beethoven wasn’t just a composer — he was a force of nature, as listeners nearly 200 years after his death can hear still in the power of his music. At the onset of his lifelong struggle with disability, and against the backdrop of political upheavals, he penned two symphonies that set him and the musical world on a new course.

The Second: Deafness and Defiance

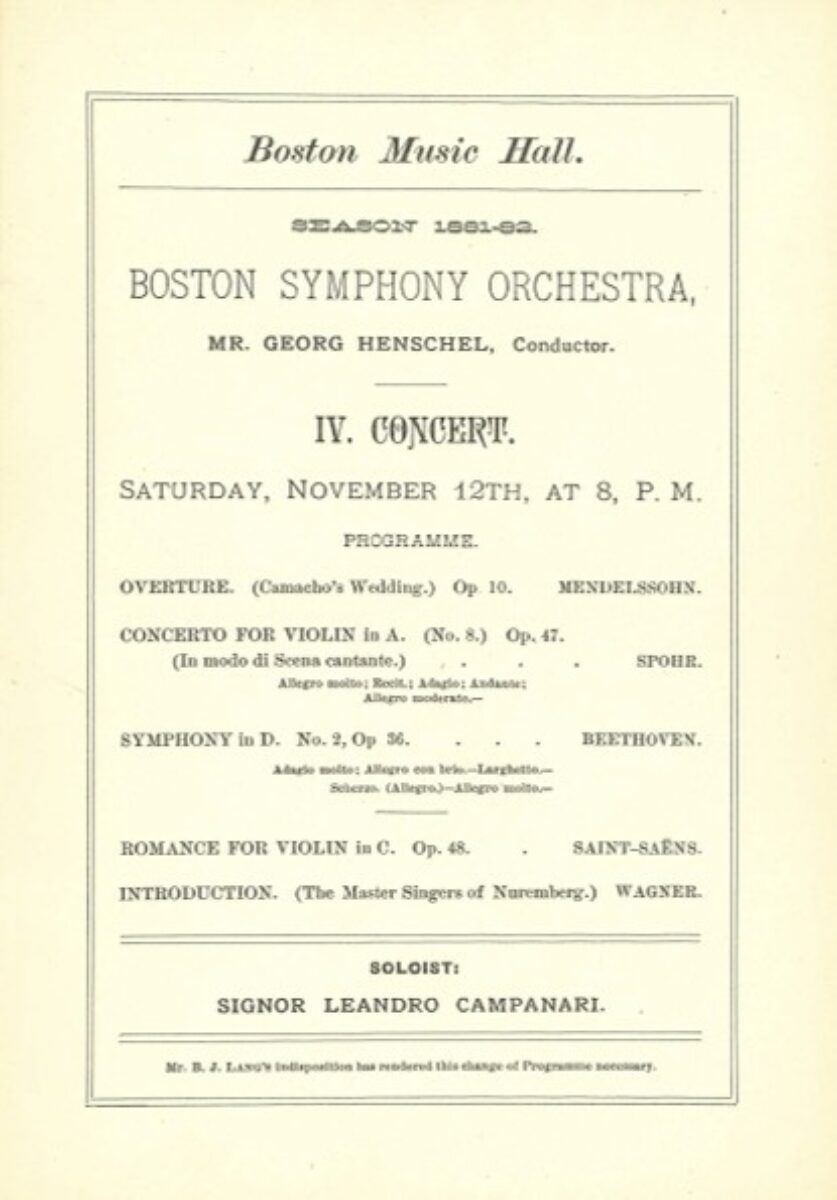

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 2 is a study in contrasts. Written during one of the darkest times in his life, it nonetheless brims with energy and optimism. Between 1801 and 1802, as he was starting on the Second Symphony, Beethoven’s encroaching hearing loss became impossible for him to ignore.

At the time, Beethoven was in his early 30s, and his star was on the rise around Europe as both a pianist and a composer. For a musician of his stature, this disability was a cruel, ironic blow. He described his despair in what is now called the "Heiligenstadt Testament," a letter nominally written to his brothers in October 1802, during his stay in the quiet village of Heiligenstadt in central Germany. In it, Beethoven admitted to moments of near-suicidal anguish.

"What a humiliation for me when someone standing next to me heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing. Such incidents drove me almost to despair, a little more of that and I would have ended my life — it was only my art that held me back."

Beethoven, in the Heiligenstadt Testament

Despite this inner turmoil, Beethoven created a symphony full of boldness and life. As Beethoven biographer Jan Swafford notes, it is the "most brash, rollicking, youthful, and nearly carefree of his symphonies."

Composed in the pastoral serenity of that small town, the Second Symphony captures both the countryside’s tranquility and Beethoven’s fierce determination to continue composing. In the Heiligenstadt Testament, he wrote, "Ah, it seemed to me impossible to leave the world until I had brought forth all that I felt was within me."

Symphony No. 2 stands as a testament to that resilience — a work that refuses to dwell in despair and instead defiantly celebrates life.

The Third: Adoration and Disillusion

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3, called the Eroica, wasn’t just another symphony — it was a game changer.

Composed in 1803 shortly after Beethoven completed his Second and wrote the Heiligenstadt Testament, the Third challenged everything people thought a symphony could say and do, stretching its length, complexity, and emotional depth.

At the heart of the Eroica is Beethoven’s admiration for Napoleon Bonaparte — or at least, what Beethoven thought Napoleon represented. To him, Napoleon was the embodiment of the revolutionary ideas of equality, liberty, democracy, and anti-monarchism. Beethoven dedicated the symphony to him, even titling it Bonaparte.

Alas, the one-sided love affair was short-lived. Beethoven’s admiration quickly curdled when Napoleon declared himself emperor of France in 1804, seemingly flying in the face of those ideals.

Famously not a very calm person, Beethoven tore the title page of the score in half.

“Is he then, too, nothing more than an ordinary human being? Now he, too ... will exalt himself above all others, become a tyrant!”

Beethoven, about Napoleon

Beethoven renamed it the Sinfonia eroica — "Heroic Symphony" — with the dedication now reading, "to celebrate the memory of a great man." Who, exactly, is this "great man" supposed to be?

The Eroica Symphony itself was nonetheless revolutionary. Even as it marked a turning point in purely musical terms, it is at the same time a testament to the power of ideals, even when heroes fall short.

Maya Shwayder is the BSO's Senior Contributing Editor and Copywriter.

References

Eroica | Beethoven & Romanticism (BSO)

Beethoven's Second

Jan Swafford program note, 2015-16 season (BSO)

Beethoven's Symphony No. 2: a sunny work peppered with brutal sforzandos (Classical Music, BBC)

Beethoven Symphony Basics at ESM (Eastman School of Music)

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 36 (Baroque Boston)